Chris’s face was set in a convincing semblance of shock. “What? I paid someone-?”

“No. You’re too smart not to realize that if you hire a shooter, blackmail might soon follow; you’d be forever in the grip of a hired killer.”

“Well, then, I obviously didn’t do it myself, and I didn’t pay anyone to do it. How did I manage it? A curse?” She laughed.

It was the most unpleasant laugh Jury had ever heard. “You did the only thing that would secure the killer’s silence: you traded murders.”

David, if it was possible, went even paler, more drawn. His skin looked stretched. “What?”

Jury did not look at him; he kept his eyes on Chris, who lost, with this last statement, her careless laughter. “Your victim pretty much came to you; I mean, you didn’t have to go all the way to London. She was your half of the bargain: Mariah Cox. Stacy Storm.”

Her mouth worked, but she said nothing for a moment. Then, “What earthly reason…? I had no reason to murder Mariah Cox. The librarian?”

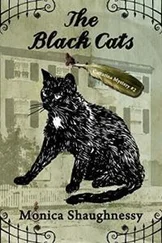

“I know you didn’t have a reason. That’s the point. There would be no motive. But the irony is, you thought you’d be killing a complete stranger. You didn’t know Stacy Storm would wind up being someone from Chesham whom you knew. You didn’t recognize her at first. But she recognized you. But at that point, facing her there in the Black Cat’s patio, you couldn’t think quick enough to rationalize the meeting. You didn’t have much choice, so you shot her anyway.

“Neither did Rose Moss have a motive for killing Kate Banks. But you did. Just as Rose Moss did have a motive for murdering Mariah Cox. For what I imagine was a very brief time, they were lovers, until Mariah called it off. Yes, it was all about to change, and not in Rose’s favor. And that, she couldn’t stand.”

The silence in the room was so dense, it was like a heavy material, weighted as the velvet curtains in Simon Santos’s living room. He stopped. No one spoke. Chris’s look of deep concentration told him her mind was working furiously to counter what he’d said.

So he said more. “That Waterstone’s receipt. You managed to get it to Rose Moss. What you were thinking was that David was the only person who could possibly have dropped it. You worked out the same thing I did: that probably no more copies of that book would be sold at that time on that day. But what you seemed to forget was that you were the only other person who possessed that receipt. You overcorrected, Chris. You tried to frame David, forgetting that you could also be pointing to yourself-”

“Chris.” David still stood, his head against the cold glass of the windowpane. He was not really speaking to her; the name came out as a breath, a sigh.

Jury went on. “But that was an easy mistake to make, since who would suspect you of murdering Kate Banks?”

Chris said, “This is all highly imaginative, but I don’t see any evidence at all.” As if to mock him, she made an elaborate survey of the room. She smiled.

Jury ignored the comment. “The Manolo Blahnik heel print was especially inventive.”

Her smile widened. She seemed to be enjoying herself now. “Then whose, if not his?”

“Well, it wasn’t a heel print, was it.” Jury walked over to the corner of the wall of shoes. “It was this.” He pulled out one of the crutches. “You could hardly ride your wheelchair to the spot where you killed Mariah Cox. So you had to use crutches-”

“What do you mean? I can’t manage on crutches!”

“Of course you can. Given your well-muscled arms, I’d say you’d gotten in a lot of practice. At first I assumed that came from getting the wheelchair about; stupid of me, as it’s electric, isn’t it? It was the one detail you didn’t think through. Strange the way the mind works: in solving one problem, we create another. You solved the problem of going to Lycrome Road in a wheelchair. If you used crutches, under that long black coat”-here Jury turned to the coatrack-“probably no one driving in a car would notice. And of course you had the advantage of the roadworks, didn’t you? Hardly anyone in the pub and no cars in the car park. But the crutches created a problem. You did a pretty good job of staying on the hard surface-the car park, the patio-but there was that one deep little print left in the earth.” Jury paused. “I’ve got to hand it to you, Chris. If anyone did think that print wasn’t the heel of a shoe, you’d be sunk, wouldn’t you? You think fast. Manolo Blahnik!

“That was the very thing that put me onto Rose Moss as the other party in this whole thing. It’s funny, or vain, but I thought Rose Moss rather fancied me. Wrong. She went out with me to find out how much I knew. She wasn’t turned on to me at all. Rose isn’t interested in men; she’s a lesbian. She thought Mariah was, too. And she isn’t like you, Chris. She hasn’t your nerve; she hasn’t your acting ability; she’ll cave in an eyeblink; she’ll give you up in a second if it means saving herself.

“Before she left me in that club, she said, ‘You mean you don’t think I ran over to Chesham in my Manolo Blahniks and shot her?’ Very careless of her. That supposed Manolo Blahnik heel print was never mentioned in the media. The only way she could have heard that was from you or police. And she certainly didn’t hear it from David or me. So it was down to you, Chris. It’s pretty much all down to you.”

In the only out-of-control moment she’d ever had around Jury, Chris Cummins picked up the teapot and threw it at the cubbyholes full of shoes, where it shattered.

Not terribly refreshed by his night at Boring’s, Melrose pulled up (yet again) in the Black Cat’s car park. He felt his life to be pretty much circumscribed by Chesham-London, London-Chesham, Chesham-London, et cetera, et cetera. He might as well buy some hovel here in Chesham and settle down.

Melrose got out of the car and trudged wearily round the corner of the pub, when he heard the cat yowling. He stopped and trudged back and opened the rear door. The cat, Morris Two, electrified by its stint in the car and its overnight stay at Boring’s, streaked out and around back to who knew where. Melrose’s life seemed to be nothing but waiting on animals. Instead of settling down in Chesham, why didn’t he get a job at the London Zoo? He pulled the cat carrier out of the backseat and plodded back.

At the side entrance he looked through the window, where Mungo and Morris stared out at him, as if he were the troublemaker here and not them. Wearily, he opened the door, wondering how in hell he was going to get Mungo in the car and back to London.

Oh, well. He went up to the bar, greeted Sally Hawkins, and asked for a double Balmenach.

“Oh, now,” she said cheekily, “a bit early in the day for a double, isn’t it, love?”

“You’re right, so give me two singles.”

She laughed and slid the glass under the optics.

Whiskey in hand, he walked over to the table by the window, peering as he did so at elderly Johnny Boy and, under the table, his dog, Horace. He sat down at the table and glared at Mungo, who wasn’t interested.

Here came Dora to slide in beside him and ask, “Did you get the cat back all right?” He could tell from her tone that the prospect of failure excited her more than that of success.

Melrose nodded. “Now, all I have to do is get you-know-who to London.”

He wasn’t fooling Mungo, who slid off the chair and trotted to the bar.

Melrose looked after him. “Maybe I could fob off Horace on Mungo’s owner.”

“Horace and Mungo don’t look a bit alike.”

“They’re both dogs, aren’t they?”

“Listen,” whispered Dora. “Mungo’s behind the bar-”

Читать дальше