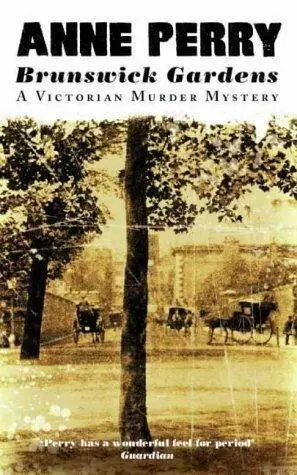

Anne Perry

Brunswick Gardens

Book 18 in the Thomas Pitt series, 1998

To Marie Coolman in Friendship

P ITT KNOCKED ON the assistant commissioner’s door and waited. It must be sensitive, and urgent, or Cornwallis would not have sent for him by telephone. Since his promotion to command of the Bow Street station Pitt had not involved himself in cases personally unless they threatened to be embarrassing to someone of importance, or else politically dangerous, such as the murder in Ashworth Hall five months earlier, in October 1890. It had ruined the attempt at some reconciliation of the Irish Problem-although with the scandal of the divorce of Katie O’Shea, citing Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Irish majority in Parliament, the whole situation was on the brink of disaster anyway.

Cornwallis opened the door himself. He was not as tall as Pitt, but lean and supple, moving easily, as if the physical strength and grace he had needed at sea were still part of his nature. So was the briefness of speech, the assumption of obedience and a certain simplicity of thought learned by one long used to the ruthlessness of the elements but unaccustomed to the devious minds of politicians and the duplicity of public manners. He was learning, but he still relied on Pitt. He looked unhappy now, his face, with its long nose and wide mouth, was set in lines of apprehension.

“Come in, Pitt.” He stood aside, holding the door back. “Sorry to require you to come so quickly, but there is a very nasty situation in Brunswick Gardens. At least, there looks to be.” He was frowning as he closed the door and walked back to his desk. It was a pleasant room, very different from the way it had been during his predecessor’s tenure. Now there were some nautical instruments on the surfaces, a sea chart of the English Channel on the far wall, and among the necessary books on law and police procedure, there were also an anthology of poetry, a novel by Jane Austen, and the Bible.

Pitt waited until Cornwallis had sat down, then did so himself. His jacket hung awkwardly because his pockets were full. Promotion had not made him conspicuously tidier.

“Yes sir?” he said enquiringly.

Cornwallis leaned back, the light shining on his head. His complete baldness became him. It was hard to imagine him differently. He never fidgeted, but when he was most concerned he put his fingers together in a steeple and held them still. He did so now.

“A young woman has met with a violent death in the home of a most respected clergyman, highly esteemed for his learned publications and very possibly in line for a bishopric: the vicar of St. Michael’s, the Reverend Ramsay Parmenter.” He took a deep breath, watching Pitt’s face. “A doctor who lives a few doors away was sent for, and on seeing the body he telephoned for the police. They came immediately, and in turn telephoned me.”

Pitt did not interrupt.

“It appears that it may be murder and Parmenter himself may have some involvement in it.” Cornwallis did not add anything as to his own feelings, but his fears were clear in the very slight pinching around his mouth and the hurt in his eyes. He regarded leadership, both moral and political, as a duty, a trust which could not be broken without terrible consequences. All his adult life so far had been spent at sea, where the captain’s word was absolute. The entire ship survived or sank on his skill and his judgment. He must be right; his orders were obeyed. To fail to do so was mutiny, punishable by death. He himself had learned to obey, and in due time he had risen to occupy that lonely pinnacle. He knew both its burdens and its privileges.

“I see,” Pitt said slowly. “Who was she, this young woman?”

“Miss Unity Bellwood,” Cornwallis replied. “A scholar of ancient languages. She was assisting Reverend Parmenter in research for a book he is writing.”

“What makes the doctor and the local police suspect murder?” Pitt asked.

Cornwallis winced and his lips pulled very slightly thinner. “Miss Bellwood was heard to cry out ‘No, no, Reverend!’ immediately before she fell, and the moment afterwards Mrs. Parmenter came out of the withdrawing room and found her lying at the bottom of the stairs. When she went to her she was already dead. Apparently she had broken her neck in the fall.”

“Who heard her cry out?”

“Several people,” Cornwallis answered bleakly. “I am afraid there is no doubt. I wish there were. It is an extremely ugly situation. Some sort of domestic tragedy, I imagine, but because of the Parmenters’ position it will become a scandal of considerable proportion if it is not handled very quickly-and with tact.”

“Thank you,” Pitt said dryly. “And the local police do not wish to keep the case?” It was a rhetorical question, asked without hope. Of course they did not. And in all probability they would not be permitted to, even had they chosen to do so. It promised to be a highly embarrassing matter for everyone concerned.

Cornwallis did not bother to answer. “Number seventeen, Brunswick Gardens,” he said laconically. “I’m sorry, Pitt.” He seemed about to add something more, then changed his mind, as if he did not know how to word it.

Pitt rose to his feet. “What is the name of the local man in charge?”

“Corbett.”

“Then I shall go and relieve Inspector Corbett of his embarrassment,” Pitt said without pleasure. “Good morning, sir.”

Cornwallis smiled at him until he reached the door, then turned back to his papers again.

Pitt telephoned the Bow Street station and gave orders that Sergeant Tellman was to meet him in Brunswick Gardens, on no account to go in ahead of him, and then took a hansom himself.

It was nearly half past eleven when he alighted in bright, chill sunshine opposite the open space and bare-leafed trees near the church. It was a short walk to number seventeen, and he saw even at twenty yards’ distance an air of difference about it. The curtains were already drawn, and there was a peculiar silence surrounding it, as if no housemaids were busy airing rooms, opening windows or scurrying in and out of the areaway, receiving deliveries.

Tellman was waiting on the pavement opposite, looking as dour as usual, his lantern-jawed face suspicious, gray eyes narrow.

“What’s happened here then?” he said grimly. “Been robbed of the family silver, have they?”

Tersely, Pitt told him what he knew, and added a warning as to the extreme tact needed.

Tellman had a sour view of wealth, privilege and established authority in general if it depended upon birth; and unless it was proved otherwise, he assumed it did. He said nothing, but his expression was eloquent.

Pitt pulled the bell at the front door and the door was opened immediately by a police constable looking profoundly unhappy. He saw that Pitt’s hair was rather too long, his pockets bulging, and his cravat lopsided, and drew in his breath to deny him entrance. He barely noticed Tellman, standing well behind.

“Superintendent Pitt,” Pitt announced himself. “And Sergeant Tellman. Mr. Cornwallis asked us to come. Is Inspector Corbett here?”

The constable’s face flooded with relief. “Yes sir, Mr. Pitt. Come in, sir. Mr. Corbett’s in the ‘all. This way.”

Pitt waited for Tellman and then closed the door. He and Tellman followed the constable across the outer vestibule into the ornate hall. The floor was a mosaic in a design of black lines and whirls on white, which Pitt thought had a distinctly Italian air. The staircase was steep and black, set against the wall on three sides and built of ebonized wood. One of the walls was tiled in deep marine blue. There was a large potted palm in a black tub directly beneath the newel post at the top. Two round white columns supported a gallery, and the main article of furniture was an exquisite Turkish screen. It was all very modern and at any other time would have been most impressive.

Читать дальше