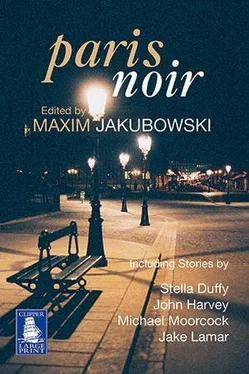

Maxim Jakubowski - Paris Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Maxim Jakubowski - Paris Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Paris Noir

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paris Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Paris Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Edited by Maxim Jakubowski, the stories range from quietly menacing to spectacularly violent, and include contributions from some of the most famous crime writers from both sides of the Atlantic, as well as the other side of the Channel.

Paris Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Paris Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I must recall how and why I became involved with Nadja. I was walking along the rue Vaugirard, preparing to turn into the Luxembourg, when I saw a woman standing in front of a butcher’s shop, desperately examining the contents of her purse. I say desperately because there were lines of great consternation on her face, as if she had misplaced and was frantically searching for the ticket that would allow her to claim a side of beef she’d pawned or left to be laundered. The weather was foul, it was early November and it was raining. The air was ugly, full of wood smoke and water, black, brown and grey. The woman, who was Nadja, was a disconcerting sight, her hair matted, stockings torn, coat soaked. I approached her immediately and asked if I might be of service.

’This is an evil afternoon,’ she said. She looked at me. ‘Can you buy me a drink? There are ravens everywhere now. Even in the shops, in the road. The government is full of them, as you no doubt are already aware. What would a government be without its ravens?’ She stared at me with horrible yellow eyes. There was no possibility of refusal. ’Of course,’ I said, and Nadja smiled, a sweet genuine smile, and gently took my arm.

Nadja had a harelip. Have I mentioned that? Or had been born with a harelip. She’d had it fixed, but that was the reason for her lopsided grin that added so inexplicably to Nadja’s desirability.

She disliked being thought of as foolish, though she often sought to contribute to the common good by committing foolish acts, such as disrobing in the Louvre in front of the Mona Lisa. For that ’act of valour’, as Nadja referred to it, she spent several days in jail, not having the money to pay the fine for being a public nuisance.

Following the incident at the Louvre, Nadja made a similar gesture of liberation on the avenue d’lena near the German Club. The Germans, she claimed, would not have her arrested; instead, Nadja said, they would pretend to ignore her. Then came the affair at the Trocadéro where Nadja disrobed and poured a bucket of red paint over her head. Neither time was she detained. The Mona Lisa episode had made her famous for the moment and her exploits of this order were no longer effective. Trocadéro was Nadja’s final mention in the newspapers. After that hers was a presence of secrets.

Nadja had a habit of laughing at the wrong moment. Someone would be in the midst of telling a story, approaching a crucial point, and Nadja would begin to laugh, softly at first, then gradually increase the level of laughter to a kind of shrill cry, shocking all those present and of course preventing the narrator from finishing his tale. The phenomenon would not occur always, but often enough so that I would be on edge whenever we were in the company of others. Several times I was forced to escort Nadja out of the room until she regained her self-control.

The unpredictable laughter was not her only social aberration. Nadja refused to be photographed. True, photographs of Nadja do exist, but they were taken surreptitiously, without her knowledge; usually when she was drunk.

Contrary to what most of my acquaintances thought at the time, Nadja was the least mysterious person I have ever met. Everything about her was obvious. Her motives were plain, she desired love, sanity, colour – all healthy pursuits. Failure on any one count can hardly be held against Nadja. Disgrace, after all, is merely a manifestation of value. The price of anything is always set in advance. Nadja made me see this. Truth is perhaps more horrible than anyone would dare admit.

She was standing there in the dream, the gun still in her hand pointing down at the body, when the cops broke in. It was Nadja with a Barbara Stanwyck hairdo in a black robe, a silk one with gold brocade on the wide lapels. ‘I shot him in the face,’ she said, ‘and he tumbled like laundry down a chute.’ Those were her exact words. They were fresh in my mind when I woke up. The name of the movie was Riffraffs that much I could remember. But it wasn’t real, it was a dream, right? I hadn’t seen Nadja in four years, and I knew who the man on the floor had to be.

One morning Nadja awoke and could not see out of her right eye. She sent a pneu asking me to meet her at the Café des Oiseaux that afternoon. ‘It’s awful and wonderful,’ Nadja said as soon as I sat down at her table. ‘There is a cloud in my eye, floating across the centre.’

‘Is it any particular colour?’ I asked.

‘Red,’ said Nadja. ‘Like a veil of blood.’

‘Perhaps it is blood,’ I said. ‘Have you made arrangements to see a doctor?’

‘Doctors can only destroy,’ Nadja said. ‘Have you a cigarette?’

I gave her one, lit it and watched her blow out the smoke.

‘Usually cigarette smoke is blue,’ she said. ‘Mixed with the red it’s actually quite beautiful, like two ghost ships passing through one another on the rolling sea.’

I asked Nadja what she intended to do about this problem.

‘Nothing.’ she said. ‘So I have one normal eye and one very interesting eye. The left shall be the practical side, the ordinary eye, useful and necessary. The right shall be the dream side, the indefinable, the exquisite and ungraspable. The right eye is my entrance to a drifting, unstable world ruled by colour and magic. Nothing is absolute there, it is a true wilderness. Covered by this thin red veil realities are made bearable by their vagueness.’

I suggested to Nadja that the presence of blood in her eye, if indeed that was what it was, might be a sign of a more serious condition, a remark that caused her to explode with laughter.

Who was Madame Sacco? Unlike Madame Blavatsky no religion was founded in her name, and also unlike the Russian she was not a charlatan. Her real name was Paulette Tanguy. born in Belleville. She set up shop as Mme Sacco on the rue des Usiness several months after the death of her third husband, an Italian, whose name I’ve forgotten, though I do not believe it was Sacco. In any case, he was seldom mentioned, and neither was she very forthcoming regarding his two predecessors. As to how Mme Sacco acquired her gift of clairvoyance, I never knew. She was never mistaken about me and I trusted her completely.

Mme Sacco knew of Nadja’s existence prior to my ever mentioning her. When Mme Sacco told me about my pre-occupation with a woman named ‘Hélène’, I was necessarily astonished. Only a day before Nadja had said to me, seemingly apropos of nothing, ‘I am Hélène.’ These women were already connected! My reputation in certain circles for naivety was apparently not altogether undeserved.

They did not, however, get along well. Nadja distrusted clairvoyants – ‘seers’ she called them, rudely. ‘Even if they know what they’re talking about,’ Nadja said, ‘even if their predictions are accurate, what right have they to inform?’

Mme Sacco sensed immediately Nadja’s hostility, and her performance in Nadja’s presence was subdued. ‘There is a great deal I could tell you about this woman,’ Mme Sacco said after Nadja had departed, ‘but she is opposed to it and therefore I cannot pursue her. I do know,’ and here Mme Sacco smiled, ‘that she is dishonest, she feigns madness and is a danger to you.’

‘Do you mean,’ I asked, ‘that Nadja is sane? That she intends to harm me?’

‘Oh no,’ Mme Sacco said, smiling even more handsomely than before, ‘she is genuinely deranged. Her pretending is the way she fools herself. As to harm, consider what you already do to yourself. This Nadja is a brief disruption in your life.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Paris Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Paris Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Paris Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.