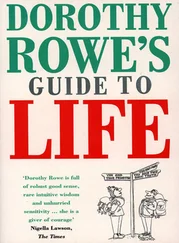

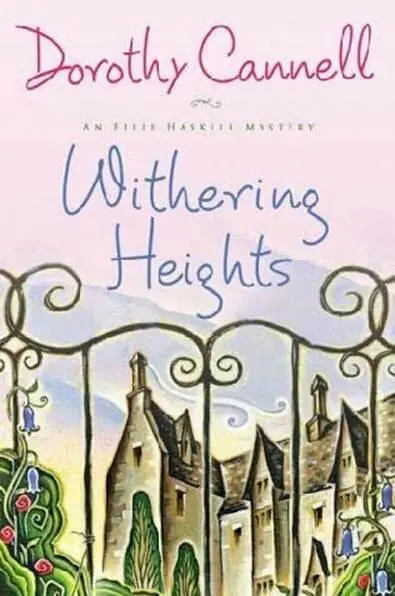

Dorothy Cannell

Withering Heights

Book 12 in the Ellie Haskell series, 2007

This book is for Master Jack, who invented the game Tree Fort versus Castle, and for the two princesses, Grace and Kate, who always cleverly escaped from the dungeon behind the sofa. With kind regards, from Mr. Small and Mrs. Tiny. And grumbling apologies from the Wicked Warlock.

The storm hurled itself against the blurred contours of the house like an angry sea. Thunder roared, lightning flared, and the wind moaned, subsiding for a moment, then whooshing back with renewed ferocity. Clouds drifted across the bruised and bloated sky. It was early afternoon, but it might well have been the dead of night, fit only for human beasts of prey and the shadowy vigils of unholy spirits denied respite beneath a sanctified churchyard earth.

A tree branch brushed my arm with skeletal fingers as I scuttled across the courtyard after parking my car in the old stable. I screeched but did not panic, until a wildly flapping moon-colored thing made a dive for me as I neared the back door. Stumbling sideways, I still became entangled in its clammy folds. No bird this, but a shroud in search of a body. (Well… it could be I overreacted a little. My husband, Ben, claims I do that sometimes.) Having fought my way free, I reassessed the situation. Perhaps I was merely dealing with a sheet blown off the line. But a very nasty evil-minded sheet, for sure.

I was glad to step into my bright kitchen at Merlin’s Court. Setting down my handbag and packages, I peeled off my raincoat and hung it on a hook in the alcove, then shook out my damp hair before weaving it back into a plait. Living on our part of the English coast, with its cliffs and rocky shoreline, we are prone to ferocious storms. But I had stayed up late the previous evening devouring the final gripping chapters of The Night Visitor , so it wasn’t surprising that my imagination had started to run amuck on the drive home through the blinding rain.

Tobias the cat was seated on the broad window ledge, where he is never supposed to be. Typically, he looked at me as though I were the one about to get into trouble. Apart from his twitching whiskers there was no sign of life. All was neat and tidy, a kitchen on its best behavior. The copper pans hung in gleaming precision from their rack. Not a cup or saucer was out of place on the Welsh dresser. No stray crumbs on the quarry-tiled floor. No plastic horse tethered to the rocking chair. No sign or sound of husband or children. They had left for London in the Land Rover the previous morning with scarcely a backward wave. The twins, Tarn and Abbey, age seven, and five-year-old Rose were to spend the next fortnight with Ben’s parents. I didn’t expect him home till early evening. The unaccustomed quiet was unnerving. Even my household helper, Mrs. Malloy, was conspicuous by her absence. Either she was occupied somewhere else in the house or she had thrown in the duster and gone home. Tobias gave me a smug look from the windowsill, as if to say how pleasant it was just being the two of us. I made myself a cup of tea and poured him a saucer of milk. He was right. What could be cozier? A woman alone with her cat, a cup of tea, and a plate of digestive biscuits.

The rain was still hammering down in a most unsuitable way for July as I seated myself at the scrubbed wood table. When a few minutes had gone by without a disembodied voice asking me to pass the sugar, I forgave the weather and was glad I had paid the second-hand bookshop in the village a visit. Under the Covers is a great place to forage for out-of-print titles. I had even grown quite keen on the smell of mildew that assaults one on entering its quiet gloom.

That day I had been buying not only for myself but also for the thirteen-year-old daughter of Ben’s cousin Tom Hopkins. I’d only met young Ariel once, a couple of years previously, at my in-laws’ flat above their greengrocer’s shop in Tottenham. Ariel was in the company of her paternal grandmother. Oblivious to the tea tray with its assortment of jam tarts and iced cakes, she’d sat with feet and hands together, looking bored to rigor mortis. Seated next to her, I did my best to bridge the child-adult gap. Mercifully, just as I was ready to abandon all hope of drawing her out of the sulks and putting something like a smile on her face, she informed me somewhat fiercely-clearly daring me to approve-that she liked black-and-white movies: especially ones set in spooky old houses. I responded casually that I enjoyed them too and didn’t object to novels of the same sort. What followed was a pleasant half-hour chat. Ariel stopped curling her lip and asked me for names of authors and titles. By the time her grandmother intimated it was time to leave, I was quite sorry to say good-bye to the whey-faced girl and asked if she would like me to sort through my collection and send her a couple of the books we had discussed. Unless her parents would object, I added responsibly.

“It’ll be all right with Dad,” said Ariel.

“And your mother?”

“Betty’s my step.” A toss of the sandy pigtails. “She won’t care what you send me.”

Not particularly heartened by this information, I got the Hopkinses’ address from my mother-in-law and a few weeks later sent off a package of books, addressing it to Tom and Betty, with a letter enclosed. I never heard back from either of them. But Ariel wrote to thank me with an enthusiasm that suggested the genie had been let out of the ink bottle. On paper she was a different child, impish and insightful. She had loved The Curse of St. Crispin’s so much that she was dying-underlined three times-to read everything else by its author. That was the beginning of our correspondence, and it became an enjoyable one for me. Over the course of the next eighteen months, I sent Ariel several more books and always looked forward to discussing them with her in letters.

Then something earthshaking happened to the Hopkins family: Tom and Betty won the lottery. They sold their semidetached home in a London suburb and bought a huge house somewhere in the north. Ben and I learned this information from his mother, but even she was not privy to their new address. And Ariel’s grandmother, who would have been a likely source of this information, had died the previous year.

Now, on this day of storm, it was six months since I had heard from Ariel. I had been thinking about her quite a lot recently, wondering how she was adjusting to her new life. Given my favorite choice of reading matter, I knew all too well that the sudden acquisition of great wealth could be a murky matter, fraught with perils for the child heiress. Ben felt that if Tom and Betty did not want people to know their whereabouts, that was their prerogative. Even so, he had agreed to ask his mother, on his current visit, if she had any updated information on where the family of three had gone to earth.

There was always the chance, I had explained while looking fervently into his marvelous blue-green eyes, that Ariel was desperately hoping I would get back in touch with her. But I had not pressed the point. Ben isn’t much of a fiction reader. He prefers cookery books, which is understandable, seeing that he has written half a dozen of his own, in addition to owning and managing a restaurant named Abigail’s in our village of Chitterton Fells.

Pouring myself another cup of tea, I realized I’d finished all the biscuits. Time slips by so fast when one is Ellie Haskell; blissfully married to the handsomest man outside of a gothic novel, with three lively children and Tobias to round out the family. Having decided to take early retirement, Tobias is underfoot much of the day, meowing about how much better things were when he was young. As if on cue, he demanded a second saucer of milk.

Читать дальше