More perplexed than ever, and with a slow but relentlessly mounting sense of panic, of time slipping through his fingers, the detective starts for home.

In Riverdale, Paul Konig has just finished hanging the portrait of Ida. He’s hung it in a commanding position, directly above the marble mantel, having removed from that spot a fine old Hudson River painting. The effect of it has been to brighten the room immeasurably. The brilliant seaside light of Montauk seems to be shimmering off the canvas. It pierces the musty, tenebrous shadows of the room like a shaft of sunlight, and Ida’s smile, glowing there above him, has a salubrious effect So much so that for those brief moments he feels very close to her. Once again her spirit is back with him in the house.

He checks his watch now. He has been checking it all day. It is nearly 6 p.m. and the countdown to 3 a.m. is already well under way. Moving about the house now, his feet have almost a spring to them. He has stocked the refrigerator with food, the first of any substance that has been in there in months. On the walls of the stairway he has hung Lolly’s three small paintings. Going up the stairs he chuckles gleefully as he views them. And upstairs in his den his fishing rods and tackle box are out, bright, gaily colored plugs lie scattered all about, oil and rags all waiting there for him to apply to the reels that he’s brought down from the attic.

Once more he glances quickly at his watch.

“But how would I remember the number?”

“I didn’t expect you to.”

“The paper, yes. I certainly sold issues of the paper, but whether or not the particular one you’re holding in your hand—”

“Uh-huh?”

“—that I have no way of knowing.”

5:55 p.m. A Small Candy Store, 49th Street Between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues.

Flynn stuffs the dog-eared, much-thumbed sheet of the Clintonian back into his pocket. Sighing, he slides wearily onto one of the red Leatherette stools before the soda fountain. “How about a lemon and lime?” he says. “Plenty of ice.”

“Would be a pleasure, Sergeant.”

Mr. Saul Siegel is a big, powerfully built man of seventy some years. He is a splendid, barrel-chested specimen with flowing white hair and somewhat Biblical mien. On the back of his head he wears a black skullcap. Flynn watches him scoop crushed ice into one of those old Coca-Cola glasses held in a steel zarf. Then the old man punches the button of a big, glass syrup dispenser and proceeds to make cold green, bubbly soda.

The vision of the skullcap, the cold green soda effervescing in a zarfed glass, the smell of the old zinc bar, and suddenly Sergeant Edward Flynn is back again, forty years or so, a little boy in Kastle’s candy store on Hester Street, stealing penny candy, while old Mr. Kastle, sorely put upon by young hooligans, cordially looks away.

Yes, Mr. Siegel’s establishment touches a nostalgic chord in Edward Flynn. It is a kind of warm, shabby hole in the wall (no bigger actually than a couple of goodsized closets) with a sliding-window counter that faces out on to the street. Having never been in there before, nevertheless the detective knows it perfectly. There in the back of the store are the same two little phone booths that Mr. Kastle had. And on the back wall is the same floor-to-ceiling magazine rack. On another wall is a glass display case crammed full with cheap toys—kites, model planes, model clay, plastic dolls, toy soldiers, jacks, penknives, packets of foreign postage stamps, and little girls’ tea sets.

By far the biggest allotment of space is given over to the bright old zinc bar with the Breyer’s ice cream signs and the faded posters depicting hamburgers and Coca-Cola. Directly above it, hanging from a long, black string, are innumerable cards of key chains, nail clippers, pipe cleaners, Zippo lighters, pencil sharpeners, rubber bands.

But it is the zinc bar itself that really captures Flynn’s heart, the splendid old bar with its shiny soda spigots, the huge inverted apothecary jars full of vividly colored syrups—the bright-red cherry, the cool green lime, the sunny yellow pineapple, the gorgeous black root beer. And there, too, a big glass cake saver full of cheese and prune Danish. And, wonder of wonders, a counter full of penny candy at the far end—boxes of jawbreakers, jelly slices, red-hots, banana candies, coconut-covered marshmallows, halavah; they’re all there. Even a bubble-gum machine—a colored ball of gum and a tiny plastic toy, all for a penny.

For a man who’s been plodding about all day, badgering a lot of irascible people, it all has a very pleasant nostalgia about it And old Siegel there, with his skullcap and his flowing white hair, looks exactly like the old rebs on Hester Street, with their tall beaver hats, their long, black frock coats, the braided forelocks streaming out from beneath the wide-brimmed hats.

Edward Flynn, as a boy, had a strange awe, a fascination, for these old men, always reading, studying day and night in the synagogue.

Sipping his lemon-lime slowly, he studies Mr. Siegel, hunched over the zinc bar, bifocals perched on the tip of his nose, and reading.

“Know the neighborhood well?” he calls to him.

Mr. Siegel glances over the rim of his bifocals, a question on his face.

“I asked if you knew the neighborhood well.”

“Been here thirty years.”

“Then you should know it.”

“I do—but it’s changing.”

“So is everything.” Flynn smiles. “Trouble?”

“Sure. But at my age, who’s running? Besides, everyone’s got trouble. Right?” Mr. Siegel smiles, and out of that craggy, patriarchal face, something like peace shines.

“Right.” Flynn nods. “What are you readin’, may I ask?”

“The Bible. Sabbath night I read the Bible.”

“What book?”

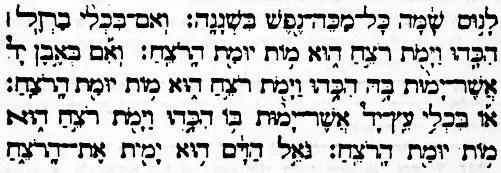

“Book of Numbers. An ancient book. Old Hebrew laws.” Flynn ponders a moment, then says, “Will you read some to me?”

There is a look of gentle amusement on the old man’s face. “You want me to read you the Bible?”

“Sure—I could use some Bible tonight.”

Mr. Siegel considers that a moment. “Well, if you could use it, who am I to deny it. Any particular passage?”

“Just where you left off will be good enough.”

Mr. Siegel is still smiling. It is an inward smile, as if something had pleased him vastly. Then, propping the bifocals on his nose, he proceeds in a quiet but curiously powerful voice.

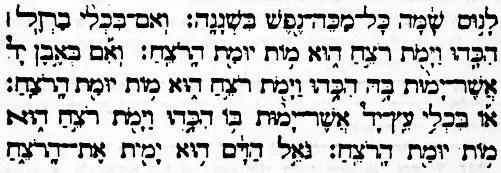

“‘And if he smite him with an instrument of iron—’”

“Not in English, please,” Flynn interrupts.

Mr. Siegel looks up again. This time the smile of amusement has turned to one of mild perplexity. “You understand Hebrew?”

“No—I just like the sound. Brings back memories.”

Mr. Siegel shrugs, nods his head, and in the next moment his soft but resonant bass rises and spreads like a shawl over the little store.

Mr. Siegel looks up, that most kindly of smiles beaming upon Flynn.

“Very pretty.” The detective nods appreciatively. “Very pretty indeed. What does it mean?”

“It’s a passage on the Cities of Refuge. The places where a criminal may or may not seek sanctuary. Would you like me to translate it for you?”

“Yes—I’d like that.”

The old man adjusts the glasses on his nose and peers back into his book:

And if he smite him with an instrument of iron, so that he die, he is a murderer: the murderer shall surely be put to death.

And if he smite him with a stone in the hand, and he die, he is a murderer: the murderer shall surely be put to death.

Читать дальше