First was Ballou, and I had to laugh at myself for thinking of him. I didn’t have a number for him, and wouldn’t have called it if I had. He probably didn’t like baseball. Even if he did, I somehow couldn’t see the two of us palling around, eating hot dogs and booing a bad call at first base. It just showed how strong if illusory the bond between us had been the previous evening for me to have thought of him at all.

The other person was Jan Keane. I didn’t have to look up her number, and I dialed it and let it ring twice, then rang off before either she or her machine could answer.

I rode the subway down to Times Square, switched to the Flushing line and rode all the way out to Shea. The cashiers were sold out, but there were plenty of kids out front with tickets to sell, and I got a decent seat, up high behind third base. Ojeda pitched a three-hit shutout and for a change the team got him some runs, and the weather was just the way it ought to be. The new kid, Jefferies, went four-for-five with a double and a home run, and he went to his left for a low liner off Van Slyke’s bat and saved Ojeda’s shutout for him.

The fellow on my right said he’d seen Willie Mays in his rookie season at the Polo Grounds, and he’d been exciting in the same way. He’d come by himself, too, and he had a lot to say over nine innings, but it was better than sitting home and listening to Scully and Garagiola and Bud Light commercials. The fellow on my left had a beer each inning until they stopped selling it in the seventh. He had an extra in the fourth, too, to make up for the half of one that he spilled on his shoes and mine. I was annoyed at having to sit there and smell it, and then I reminded myself that I had a lady friend who generally smelled of beer when she didn’t smell of scotch, and that I’d spent the previous night voluntarily breathing stale beer fumes in a lowlife saloon and had a grand time of it. So I had no real reason to sulk if my neighbor wanted to sink a few while he watched the home team win one.

I had a couple of hot dogs myself, and drank a root beer, and stood up for the national anthem and the seventh-inning stretch, and to give Ojeda a hand when he got the last Pirate to swing at a curveball low and away. “They’ll roll right over the Dodgers in the playoffs,” my new friend assured me. “But I don’t know about Oakland.”

I’d made a dinner date with Willa earlier. I stopped at my hotel to shave and put on a suit, then went over to her place. She had her hair braided again, and the braid coiled across her forehead like a tiara. I told her how nice it looked.

She still had the flowers on the kitchen table. They were past their prime, and some were losing their petals. I mentioned this, and she said she wanted to keep them another day. “It seems cruel to throw them out,” she said.

She tasted of booze when I kissed her, and she had a small scotch while we decided where to go. We both wanted meat, so I suggested the Slate, a steak house on Tenth Avenue that always drew a lot of cops from Midtown North and John Jay College.

We walked over there and got a table in front near the bar. I didn’t see anyone I recognized, but several faces were vaguely familiar and almost every man in the room looked to be on the job. If anyone had been fool enough to hold the place up, he’d have been surrounded by men with drawn revolvers, a fair percentage of them half in the bag.

I mentioned this to Willa, and she tried to calculate our chances of being gunned down in crossfire. “A few years ago,” she said, “I wouldn’t have been able to sit still in a place like this.”

“For fear of being caught in a crossfire?”

“For fear they’d be shooting at me on purpose. It’s still hard for me to believe I’m dating a guy who used to be a cop.”

“Did you have a lot of trouble with cops?”

“Well, I lost two teeth,” she said, and fingered the two upper incisors that replaced the ones knocked out in Chicago. “And we were always getting hassled. We were presumably undercover, but we always figured the FBI had somebody in the organization reporting to them, and I can’t tell you the number of times the Feebies showed up to question me. Or to have long sessions with the neighbors.”

“That must have been a hell of a way to live.”

“It was crazy. But it almost killed me to leave.”

“They wouldn’t let you go?”

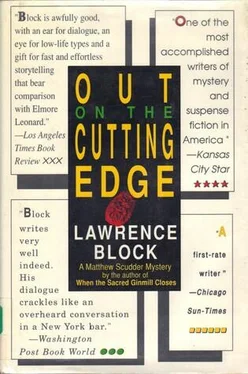

“No, it wasn’t like that. But the PCP gave my life all the meaning it had for a whole lot of years, and when I left it was like admitting all those years were a waste. And on top of that I would find myself doubting my actions. I would think that the PCP was right, and that I was just copping out, and missing my chance to make a difference in the world. That was what kept you sucked in, you know. The chance it gave you to see yourself as being one of the ones who mattered, out there on the cutting edge of history.”

We took our time over dinner. She had a sirloin and a baked potato. I ordered the mixed grill, and we split a Caesar salad. She started off with a scotch, then drank red wine with her dinner. I got a cup of coffee right away and let them keep filling it up for me. She wanted a pony of Armagnac with her coffee. The waitress came back and said the bartender didn’t have any, so she settled for a cognac. It couldn’t have been too bad, because she drank it and ordered a second one.

The check came to a fairly impressive sum. She wanted to split it and I didn’t work too hard trying to talk her out of it. “Actually,” she said, checking the waitress’s arithmetic, “I should be paying about two-thirds of this. More than that. I had a million drinks and you had a cup of coffee.”

“Cut it out.”

“And my entrée was more than yours.”

I told her to stop it, and we halved the check and the tip. Outside, she wanted to walk a little to clear her head. It was a little late for panhandlers, but some of them were still hard at it. I passed out a few dollars. The wild-eyed woman in the shawl got one of them. She had her baby in her arms, but I didn’t see her other child, and I tried not to wonder where it had gone to.

We walked downtown a few blocks and I asked Willa if she’d mind stopping at Paris Green. She looked at me, amused. “For a guy who doesn’t drink,” she said, “you sure do a lot of barhopping.”

“Somebody I want to talk to.”

We cut across to Ninth, walked down to Paris Green and took seats at the bar. My friend with the bird’s-nest beard wasn’t working, and the fellow on duty was no one I’d seen before. He was very young, with a lot of curly hair and a sort of vague and unfocused look about him. He didn’t know how I could get hold of the other bartender. I went over and talked to the manager, describing the bartender I was looking for.

“That’s Gary,” he said. “He’s not working tonight. Come around tomorrow, I think he’s working tomorrow.”

I asked if he had a number for him. He said he couldn’t give that out. I asked if he’d call Gary for me and see if he’d be willing to take the call.

“I really don’t have time for that,” he said. “I’m trying to run a restaurant here.”

If I still carried a badge he’d have given me the number with no argument. If I’d been Mickey Ballou I’d have come back with a couple of friends and let him watch while we threw all his chairs and tables out into the street. There was another way, I could give him five or ten dollars for his time, but somehow that went against the grain.

I said, “Make the phone call.”

“I just told you—”

“I know what you told me. Either make the phone call for me or give me the fucking number.”

I don’t know what the hell I could have done if he’d refused, but something in my voice or face must have gotten through to him. He said, “Just a moment,” and disappeared into the back. I went and stood next to Willa, who was working on a brandy. She wanted to know if everything was all right. I told her everything was fine.

Читать дальше