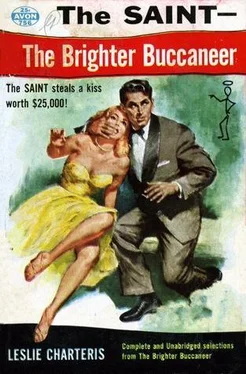

Leslie Charteris - The Brighter Buccaneer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - The Brighter Buccaneer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1933, Издательство: Doubleday, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Brighter Buccaneer

- Автор:

- Издательство:Doubleday

- Жанр:

- Год:1933

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Brighter Buccaneer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Brighter Buccaneer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Brighter Buccaneer — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Brighter Buccaneer», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Hill Billy's the name," said the Saint, "and I guess it's good for a hundred."

"Two hundred and fifty pounds to one hundred for Mr. Templar," said Mackintyre lusciously, and watched his clerk entering up the bet.

When he looked up the Saint had gone.

Tilbury dropped back to seven to two, and Hill Billy stayed solid at two and a half. Just before the "off" Mr. Mackintyre shouted, "Six to one, Rickaway," and had the satisfaction of seeing the odds go down before the recorder closed his notebook.

He mopped his brow, and found Mr. Lesbon beside him.

"I wired off five hundred pounds to ten different offices," said Lesbon. "A little more of this and I'll be moving into Park Lane. When the girl came to see me I nearly fainted. What does that man Templar take us for?"

"I don't know," said Mr. Mackintyre phlegmatically.

A general bellow from the crowd announced the "off," and Mr. Mackintyre mounted his stool and watched the race through his field-glasses.

"Tilbury's jumped off in front; Hill Billy's third, and Rickaway's going well on the outside… Rickaway's moving up, and Hill Billy's on a tight rein… Hill Billy's gone up to second. The rest of the field's packed behind, but they don't look like springing any surprises… Tilbury's finished. He's falling back. Hill Billy leads, Mandrake running second, Rickaway half a length behind with plenty in hand… Penterham's using the whip, and Rickaway's picking up. He's level with Mandrake — no, he's got it by a short head. Hill Billy's a length in front, and they're putting everything in for the finish."

The roar of the crowd grew louder as the field entered the last furlong. Mackintyre raised his voice.

"Mandrake's out of it, and Rickaway's coming up! Hill Billy's flat out with Rickaway's nose at his saddle… Hill Billy's making a race of it. It's neck-and-neck now. Penterham left it a bit late. Rickaway's gaining slowly —"

The yelling of the crowd rose to a final crescendo, and suddenly died away. Mr. Mackintyre dropped his glasses and stepped down from his perch.

"Well," he said comfortably,"that's three thousand pounds."

The two men shook hands gravely and turned to find Simon Templar drifting towards them with a thin cigar in his mouth.

"Too bad about Hill Billy, Mr. Templar," remarked Mackintyre succulently. "Rickaway only did it by a neck, though I won't say he mightn't have done better if he'd started his sprint a bit sooner."

Simon Templar removed his cigar.

"Oh, I don't know," he said. "As a matter of fact, I rather changed my mind about Hill Billy's chance just before the 'off.' I was over at the telegraph office, and I didn't think I'd be able to reach you in time, so I wired another bet to your London office. Only a small one — six hundred pounds, if you want to know. I hope Vincent's winnings will stand it." He beamed seraphically at Mr. Lesbon, whose face had suddenly gone a sickly grey. "Of course you recognised Miss Holm — she isn't easy to forget, and I saw you noticing her at the Savoy the other night."

There was an awful silence.

"By the way," said the Saint, patting Mr. Lesbon affably on the shoulder, "she tells me you've got hot slimy hands. Apart from that, your technique makes Clark Gable look like something the cat brought in. Just a friendly tip, old dear."

He waved to the two stupefied men and wandered away; they stood gaping dumbly at his back.

It was Mr. Lesbon who spoke first, after a long and pregnant interval.

"Of course you won't settle, Joe," he said half-heartedly.

"Won't I?" snarled Mr. Mackintyre. "And let him have me up before Tattersall's Committee for welshing? I've got to settle, you fool!"

Mr. Mackintyre choked.

Then he cleared his throat. He had a great deal more to say, and he wanted to say it distinctly.

5. The Tough Egg

Chief inspector Teal caught Larry the Stick at Newcastle trying to board an outward-bound Swedish timber ship. He did not find the fifty thousand pounds' worth of bonds and jewellery which Larry took from the Temple Lane Safe Deposit; but it may truthfully be reported that no one was more surprised about that than Larry himself.

They broke open the battered leather suit-case to which Larry was clinging as affectionately as if it contained the keys of the Bank of England, and found in it a cardboard box which was packed to bursting-point with what must have been one of the finest collections of small pebbles and old newspapers to which any burglar had ever attached himself; and Larry stared at it with glazed and incredulous eyes.

"Is one of you busies saving up for a rainy day?" he demanded, when he could speak; and Mr. Teal was not amused.

"No one's been to that bag except when you saw us open it," he said shortly. "Come on, Larry — let's hear where you hid the stuff."

"I didn't hide it," said Larry flatly. He was prepared to say more, but suddenly he shut his mouth. He could be an immensely philosophic man when there was nothing left for him to do except to be philosophic, and one of his major problems had certainly been solved for him very providentially. "I hadn't anything to hide, Mr. Teal. If you'd only let me explain things I could've saved you busting a perfickly good lock and making me miss my boat."

Mr. Teal tilted back his bowler hat with a kind of weary patience.

"Better make it short, Larry," he said. "The night watchman saw you before you coshed him, and he said he'd recognize you again."

"He must've been seeing things," asserted Larry. "Now, if you want to know all about it, Mr. Teal, I saw the doctor the other day, and he told me I was run down. 'What you want, Larry, is a nice holiday,' he says — not that I'd let anyone call me by my first name, you understand, but this doc is quite a good-class gentleman. 'What you want is a holiday,' he says. 'Why don't you take a sea voyage?' So, seeing I've got an old aunt in Sweden, I thought I'd pay her a visit. Naturally, I thought, the old lady would like to see some newspapers and read how things were going in the old country —"

"And what did she want the stones for?" inquired Teal politely. "Is she making a rock garden?"

"Oh, them?" said Larry innocently. "Them was for my uncle. He's a geo — geo —"

"Geologist is the word you want," said the detective, without smiling. "Now let's go back to London, and you can write all that down and sign it."

They went back to London with a resigned but still chatty cracksman, though the party lacked some of the high spirits which might have accompanied it. The most puzzled member of it was undoubtedly Larry the Stick, and he spent a good deal of time on the journey trying to think how it could have happened.

He knew that the bonds and jewels had been packed in his suit-case when he left London, for he had gone straight back to his lodgings after he left the Temple Lane Safe Deposit and stowed them away in the bag that was already half-filled in anticipation of an early departure. He had dozed in his chair for a few hours, and caught the 7.25 from King's Cross — the bag had never been out of his sight. Except… once during the morning he had succumbed to a not unreasonable thirst, and spent half an hour in the restaurant car in earnest collaboration with a bottle of Worthington. But there was no sign of his bag having been tampered with when he came back, and he had seen no familiar face on the train.

It was one of the most mystifying things that had ever happened to him, and the fact that the police case against him had been considerably weakened by his bereavement was a somewhat dubious compensation.

Chief Inspector Teal reached London with a theory of his own. He expounded it to the Assistant Commissioner without enthusiasm.

"I'm afraid there's no doubt that Larry's telling the truth," he said. "He's no idea what happened to the swag, but I have. Nobody double-crossed him, because he always works alone, and he hasn't any enemies that I know of. There's just one man who might have done it — you know who I mean."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Brighter Buccaneer»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Brighter Buccaneer» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Brighter Buccaneer» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.