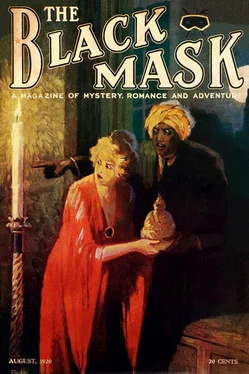

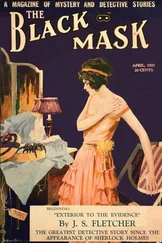

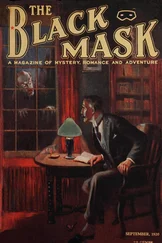

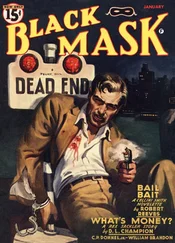

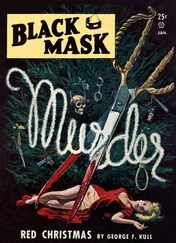

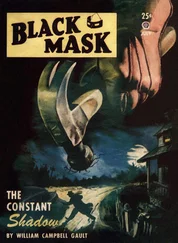

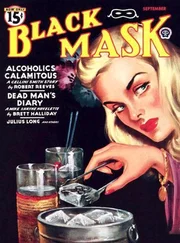

J. Thorne - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «J. Thorne - The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1920, Издательство: Pro-distributors Publishing Company, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pro-distributors Publishing Company

- Жанр:

- Год:1920

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920): краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920) — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We had many visitors. Mostly they were men and women in the late thirties and forties. Although much of the conversation was beyond me I liked to sit quietly in the large living room and listen to the callers. I believe it was during this period that my views relative to the Law of Compensation took coherent shape.

While my foster-parents' friends discussed every subject under the sun there was one topic upon which each and all spoke fluently and often — their ailments. Everybody seemed to have something the matter with him or her. Mrs. Austin had neuralgia, Mr. Hawkins had a heart lesion, Mr. Swift suffered from constant, inexplicable pains in the back, Mrs. Steffens brooded about an incipient goitre, Mr. Holliday was worried with a tenacious cough and Mrs. Taylor's stoutness preyed on her mind.

Of all the visitor's my favorite was John Shelton, a school principal. He had no particular malady except that his eyes gave him trouble. He complained that they hurt when he read at night.

"Mr. Shelton," I said to him one evening when we happened to be alone in the living room, "do all people get sick when they get to be thirty or thereabouts?"

He laughed good-naturedly.

"That's a funny question. Of course, not."

"Why is it, then," I asked, "that people of that age are always talking about their ailments or looking worried? There's you, for example. Why aren't you happy all the time, like I am?"

"Oh, you're young," he replied. "You have no cares, no responsibilities. There's nothing to keep you from being contented twenty-four hours in the day."

"That's what I thought," replied. "As you grow older you get the things that make you unhappy."

"That's the way of life," he answered soberly. "Take my advice, young man, and get all the pleasure you can out of your boyhood. The sweetness of living is now yours."

Suddenly he turned with a laugh and said:

"Paul, do you know where your heart is?"

"Certainly," and I struck my left side with the hand.

"You're wrong." he smiled. "It's here!" He pointed to a spot three inches to the right of the place I had indicated and two inches lower.

"Know where your stomach is?"

I showed him where I thought it was.

Apparently I knew less about the stomach than I did about the heart. I was somewhat ashamed and told Shelton that we had just started the study of anatomy at high school.

"Books will never tell you just where your vital organs are," he said, "and the longer you remain in ignorance the better off you will be. When you do learn exactly where your stomach is, it will be the finger of pain pointing it out. Suffering is the perfect instructor in anatomy."

Just at that time other callers arrived and the questions trembling on the point of my tongue went unasked. Afterward he avoided the subject of anatomy.

III

The next three years passed rapidly, happy, joyous, unrestrained years. My plan of life was rapidly developing. I was determined to squeeze out of existence every drop of happiness it contained before the location of my heart was known to me with exactness.

When I was not playing I observed men and women along novel lines. I read faces for signs of content and unhappiness. I fell into the habit of checking up the number of times I had seen this or that individual in a month, how many times he had been smiling, how many limes he had been frowning, how often he had appeared at ease, how often worried. I did not let these studies interfere with my main program. I sought enjoyment with almost hysterical insistence. I would permit nothing to depress me, nothing to divert me from my purpose.

At eighteen I was sent to college. Because knowledge came easily I was a good student. Had it been otherwise I would have quit the pursuit of learning and sought less strenuous occupation.

I had a room-mate, Arthur Gates, a jolly, harum-scarum, rich man's son, who worshipped at the shrine of Play as feverishly as L Although he was not lacking in serious moments he was dumfounded, I know, when I told him my secret.

We had been in the history lecture class together that afternoon when the instructor suddenly turned pale, clutched his coat lapel and fell at the foot of his desk. He was a man of about forty and seemingly had been in good health. We helped take him home. I learned that he was a sufferer from angina pectoris , an unusually painful affliction of the heart.

In our room that evening Gates mentioned the instructor's illness.

"That could never happen to me," I remarked.

"Why?" he asked. "Have you a guarantee on your heart?"

"No," I answered slowly, "but I shall not live that long."

"What are you talking about? Duckworth isn't over forty-five."

"When my forty-fifth birthday comes around." I replied calmly, "I know I will have been dead ten years."

Gates laughed.

"Been to see a fortune teller?" he jeered.

"No, but on the day that I finish my thirty-fifth year I shall kill myself."

"How do you know," asked my room-mate, "that you won't get angina before you're thirty-five?"

"I don't, but it's hardly likely. The percentage is in my favor."

Gates was beginning to be impressed with the fact that I was serious. He gazed at me with puzzled eyes.

"Arthur," I said. "I want you to listen to me for a few moments. What I am about to tell you I have told to no other person and will tell to no other person. I feel that I must unbosom myself to someone. Will you listen seriously?"

He nodded. I went on:

"I am now twenty-one years old. I have excellent health, plenty of money, no troubles, domestic or otherwise, and what are regarded as excellent prospects. Yet, I tell you in cold blood that at 7:32 a. m., on April 6th, 1920, I shall end my life. That will be the exact hour of my birth, thirty-five years before. Just how I shall do it I do not yet know. Naturally I shall take the least painful and least unpleasant way."

"But why?" interrupted Gates, who had been watching me with strange fascination.

"That," I replied, "will develop in the course of what I am about to tell you. Understand I am not trying to influence you in any way. I know that you will not agree with me. When I was a boy my father and mother both died in great agony. I can see them now, gray with torture, their pallid features furrowed with the lines of suffering and the perspiration of pain on their foreheads. I can still hear my father pleading for death — death that stood outside the door leeringly biding its time."

"Afterwards I lived for many years at the home of an uncle. There I saw more suffering. I began asking myself these questions — Is life worth living? If so, how long should one live? When do the tears of existence begin to outweigh the smiles? At what point in the span do the joys of carrying on no longer balance the sorrows?"

"In seeking answers to my interrogations I made a close and detailed study of scores of men and women. I watched their faces and searched their souls. I have continued the researches at college, coldly, scientifically. I have tables and charts and masses of statistics, and the conclusions I reached by observation have been borne out by analysis and precise data. And my conclusion is this: The average life after thirty-five is not worth living."

I saw a "why" trembling on Gates' lips and went on:

"The span of human life is seventy years. In the first thirty-five we sow, in the other thirty-five we reap. It is the Law of Compensation. The pleasures and enjoyment of existence are freely bestowed in the first half of the span, but the bills begin coming in with the thirty-sixth year. I have made up my mind not to pay. When the collector comes I will be out."

My room-mate shook his head.

"That's certainly a bizarre theory," he said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Mask Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 5 - August 1920)» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.