Introduction

Top-shelf noir

When Johnny Temple, the publisher of Akashic Books, approached me with the idea of editing a sequel of sorts to D.C. Noir, our best-selling 2005 anthology of original Washington crime fiction, I told him I’d need to think on it. After all, I felt as if we’d covered the waterfront with that collection, and wasn’t particularly interested in being involved with a second-tier batch of stories meant to cash in on the original. Johnny assured me that this would not be the case. What he was shooting for was the top-shelf of Washington short fiction, previously published stories of a noirish bent by some of the best writers who have come out of or written about this town. Now I was interested.

What I found, once I was in the hunt, was that it was not as easy as I imagined it would be to find stories that would fit the bill. I first spent several days at the Washingtoniana Room of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, searching and reading, and found only a couple of stories that I liked. A young man who worked there put me in contact with a Margaret Goodbody, formerly of the MLK, now with the Bethesda Library in Montgomery County, Maryland. Ms. Goodbody suggested stories by Julian Mazor, which I eventually used, and helpfully pointed me in the direction of several databases and private collections. It’s fair to say she got me going, and I’m very grateful for her assistance. In addition, Ibrahim Ahmad of Akashic Books was particularly diligent in researching, coordinating, and reviewing material that he felt would make a good fit for our project.

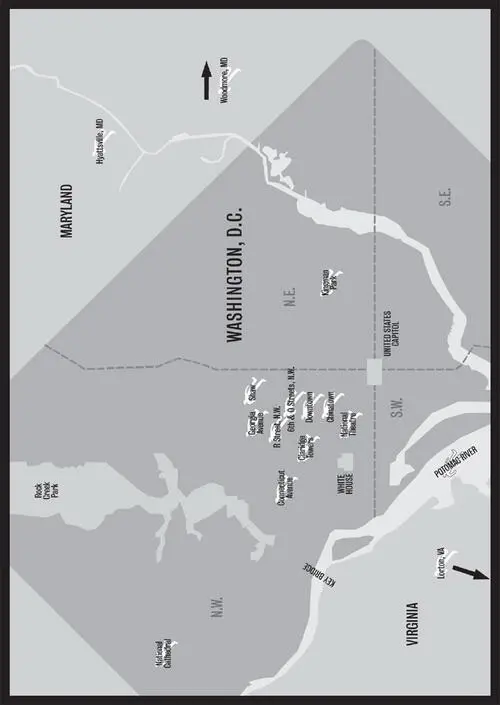

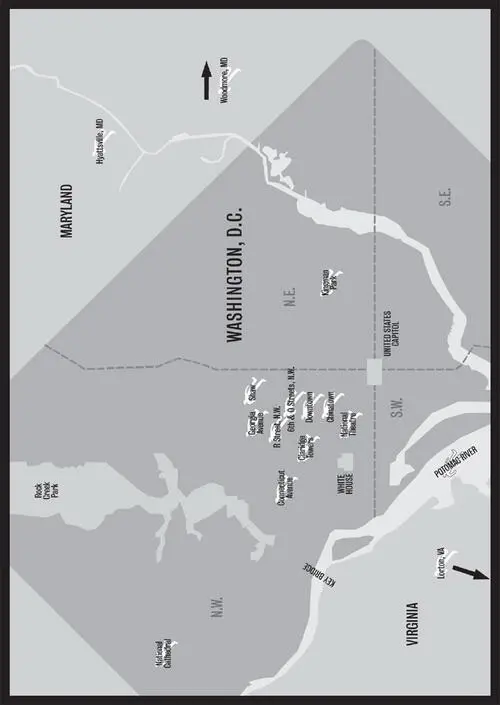

What Johnny Temple and I began to envision, as we got deeper into it, was a century-long overview of D.C. fiction that would focus on issues of race, ethnicity, politics, class, and the attendant struggles and changes that occurred in various eras of our history. In the finished product, the stories are arranged chronologically, in the order in which they were originally published, and geographically, by neighborhood or locale, to give you, in effect, a timeline and map of our literary city.

I have to say, I am very pleased with what we have compiled. The stories are high quality, the list of authors reads like lit royalty, and the package is handsome. Allow me also to give a nod to my friend, the accomplished photographer Jim Saah, whose evocative work once again appears on our cover. D.C. Noir 2: The Classics is a keeper.

Now, to the contributors.

The first name on my wish list was Edward P. Jones. I consider him to be the finest fiction writer to ever come out of Washington, D.C., and in the bargain he is a homegrown talent and graduate of Cardozo High School. From the collection All Aunt Hagar’s Children, we chose “A Rich Man,” which is not only a stunning piece of craftsmanship, but is full noir in its depiction of a man trapped inside a cage of his own making.

I next sought a contribution from Marita Golden, one of our most celebrated, popular, and talented local authors, and reached her in her office at the University of the District of Columbia, where she is currently serving as Writer-in-Residence. Ms. Golden’s selection comes from After, her critically acclaimed novel on a police shooting and its psychological aftermath.

Our earliest-set tale was written by Paul Laurence Dunbar. (This is a fitting time to address our definition of “noir,” which, with respect to this collection, is rather broad, particularly for the older stories. I tend to define noir by its psychological elements, rather than its crime elements or “visuals,” which come from our natural association with film noir. Remember, it was the French who told us what noir “was” to begin with, a half-century after the publication of some of our early stories. As usual, I have digressed.) “A Council of State” is a telling and troubling story of the reality of racial politics in the Federal City at the turn of the last century. Dunbar, the son of escaped slaves, was the first eminent African American poet, as well as an accomplished short story writer, playwright, essayist, and novelist. Raised in Dayton, Ohio, he lived for a time in the LeDroit Park neighborhood of D.C., attended Howard University, and worked for about year at the Library of Congress, where the dusty environs were said to have worsened the tuberculosis that would end his life at the age of thirty-three. Dunbar Senior High School, D.C.’s first one exclusively for black teenagers — and for decades a model of academic achievement — was named in his honor, as were similar high schools in Baltimore and Fort Worth, Texas. It is fitting that his work be included here.

Julian Mayfield grew up in D.C. and was a notable actor, playwright, director, and novelist, as well as a Writer-in-Residence at Howard University and a political activist. He also cowrote, with Ruby Dee and Jules Dassin, the screenplay for the film Up Tight! Mr. Mayfield’s story, “The Last Days of Duncan Street,” is an affecting time-capsule snapshot of boys and a neighborhood.

Larry Neal was a writer, poet, and, with Amiri Baraka, one of the most significant members of the Black Arts Movement during the 1960s. For several years he was Executive Director of the District of Columbia Commission on the Arts and Humanities. His story, “Our Bright Tomorrows,” is a meditation on loss, revolution, and the passage of time.

Julian Mazor, a graduate of Woodrow Wilson Senior High School in the District (as is publisher Johnny Temple), made a splash in the literary world with his outstanding collection Washington and Baltimore, brought out by Knopf in 1968. Several of its stories were printed in the New Yorker, including our tale, “Washington,” about a traveling young white man who gets off a bus in a black D.C. neighborhood and his ensuing afternoon adventure.

Elizabeth Hand moved to Washington in 1975 to attend Catholic University, where she studied playwriting and cultural anthropology. She worked in those years and beyond at the Smithsonian and was an active participant in the city’s storied punk movement. Her novels and short fiction carry shades of autobiography and cross genre lines gracefully, with a reoccurring interest in outsider artists. “Wonderwall,” harrowing and nakedly honest, is one of my very favorite D.C. short stories.

The Washington Post once called James Grady, fittingly, a “local legend.” His early career as an investigative journalist and an innate curiosity for what lies beneath resulted in a deep understanding of the workings of this town that is evidenced in his auspicious body of work, which includes fourteen novels to date and numerous screenplays and short stories. “Kiss the Sky,” set in the now-closed Lorton Correctional Complex, is a good example of Grady’s ear for dialogue, rhythmic pacing, and cinematic eye.

Ward Just is one of the finest authors to ever write about political Washington and, by extension, America. Many have traced his literary lineage to Henry James and Ernest Hemingway. I would add Graham Greene to the mix, in that Mr. Just is as concerned with the cost of a life devoted to politics and the spy game as he is the mechanics. “Nora,” from the original edition of his story collection The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert, is a haunting example of his singular talent.

Benjamin M. Schutz was the author of seven Washington-based mystery novels and numerous short stories, for which he won both the Edgar Award and three Shamus Awards. He was a noted forensic and clinical psychologist whose knowledge of the human condition was strongly present in his fiction writing. Here we have “Christmas in Dodge City,” which depicts a night in the life of a Cold Case squad detective. Mr. Schutz, who passed away early in 2008, will be missed.

Читать дальше