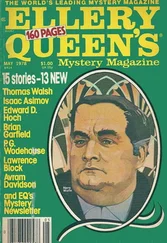

Lawrence Block

The Ehrengraf Appointment

“Dame Fortune is a fickle gypsy,

And always blind, and often tipsy.”

— William Mackworth Praed

Martin Ehrengraf was walking jauntily down the courthouse steps when a taller and bulkier man caught up with him. “Glorious day,” the man said. “Simply a glorious day.”

Ehrengraf nodded. It was indeed a glorious day, the sort of autumn afternoon that made men recall football weekends. Ehrengraf had just been thinking that he’d like a piece of hot apple pie with a slab of sharp cheddar on it. He rarely thought about apple pie and almost never wanted cheese on it, but it was that sort of day.

“I’m Cutliffe,” the man said. “Hudson Cutliffe, of Marquardt, Stoner, and Cutliffe.”

“Ehrengraf,” said Ehrengraf.

“Yes, I know. Oh, believe me, I know.” Cutliffe gave what he doubtless considered a hearty chuckle. “Imagine running into Martin Ehrengraf himself, standing in line for an IDC appointment just like everybody else.”

“Every man is entitled to a proper defense,” Ehrengraf said stiffly. “It’s a guaranteed right in a free society.”

“Yes, to be sure, but—”

“Indigent defendants have attorneys appointed by the court. Our system here calls for attorneys to make themselves available at specified intervals for such appointments, rather than entrust such cases to a public defender.”

“I quite understand,” Cutliffe said. “Why, I was just appointed to an IDC case myself, some luckless chap who stole a satchel full of meat from a supermarket. Choice cuts, too — lamb chops, filet mignon. You just about have to steal them these days, don’t you?”

Ehrengraf, a recent convert to vegetarianism, offered a thin-lipped smile and thought about pie and cheese.

“But Martin Ehrengraf himself,” Cutliffe went on. “One no more thinks of you in this context than one imagines a glamorous Hollywood actress going to the bathroom. Martin Ehrengraf, the dapper and debonair lawyer who hardly ever appears in court. The man who only collects a fee if he wins. Is that really true, by the way? You actually take murder cases on a contingency basis?”

“That’s correct.”

“Extraordinary. I don’t see how you can possibly afford to operate that way.”

“It’s quite simple,” Ehrengraf said.

“Oh?”

His smile was fuller than before. “I always win,” he said. “It’s simplicity itself.”

“And yet you rarely appear in court.”

“Sometimes one can work more effectively behind the scenes.”

“And when your client wins his freedom—”

“I’m paid in full,” Ehrengraf said.

“Your fees are high, I understand.”

“Exceedingly high.”

“And your clients almost always get off.”

“They’re always innocent,” Ehrengraf said. “That does help.”

Hudson Cutliffe laughed richly, as if to suggest that the idea of bringing guilt and innocence into a discussion of legal procedures was amusing. “Well, this will be a switch for you,” he said at length. “You were assigned the Protter case, weren’t you?”

“Mr. Protter is my client, yes.”

“Hardly a typical Ehrengraf case, is it? Man gets drunk, beats his wife to death, passes out, and sleeps it off, then wakes up and sees what he’s done and calls the police. Bit of luck for you, wouldn’t you say?”

“Oh?”

“Won’t take up too much of your time. You’ll plead him guilty to manslaughter, get a reduced sentence on grounds of his previous clean record, and then Protter’ll do a year or two in prison while you go about your business.”

“You think that’s the course to pursue, Mr. Cutliffe?”

“It’s what anyone would do.”

“Almost anyone,” said Ehrengraf.

“And there’s no reason to make work for yourself, is there?” Cutliffe winked. “These IDC cases — I don’t know why they pay us at all, as small as the fees are. A hundred and seventy-five dollars isn’t much of an all-inclusive fee for a legal defense, is it? Wouldn’t you say your average fee runs a bit higher than that?”

“Quite a bit higher.”

“But there are compensations. It’s the same hundred and seventy-five dollars whether you plead your client or stand trial, let alone win. A far cry from your usual system, eh, Ehrengraf? You don’t have to win to get paid.”

“I do,” Ehrengraf said.

“How’s that?”

“If I lose the case, I’ll donate the fee to charity.”

“If you lose? But you’ll plead him to manslaughter, won’t you?”

“Certainly not.”

“Then what will you do?”

“I’ll plead him innocent.”

“Innocent?”

“Of course. The man never killed anyone.”

“But—” Cutliffe inclined his head, dropped his voice. “You know the man? You have some special information about the case?”

“I’ve never met him and know only what I’ve read in the newspapers.”

“Then how can you say he’s innocent?”

“He’s my client.”

“So?”

“I do not represent the guilty,” Ehrengraf said. “My clients are innocent, Mr. Cutliffe, and Arnold Protter is a client of mine, and I intend to earn my fee as his attorney, however inadequate that fee may be. I did not seek appointment, Mr. Cutliffe, but that appointment is a sacred trust, sir, and I shall justify that trust. Good day, Mr. Cutliffe.”

“They said they’d said get me a lawyer and it wouldn’t cost me nothing,” Arnold Protter said. “I guess you’re it, huh?”

“Indeed,” said Ehrengraf. He glanced around the sordid little jail cell, then cast an eye on his new client. Arnold Protter was a thickset round-shouldered man in his late thirties with the ample belly of a beer drinker and the red nose of a whiskey drinker. His pudgy face recalled the Pillsbury Dough Boy. His hands, too, were pudgy, and he held them out in front of his red nose and studied them in wonder.

“These were the hands that did it,” he said.

“Nonsense.”

“How’s that?”

“Perhaps you’d better tell me what happened,” Ehrengraf suggested. “The night your wife was killed.”

“It’s hard to remember,” Protter said.

“I’m sure it is.”

“What it was, it was an ordinary kind of a night. Me and Gretch had a beer or two during the afternoon, just passing time while we watched television. Then we ordered up a pizza and had a couple more with it, and then we settled in for the evening and started hitting the boilermakers. You know, a shot and a beer. First thing you know, we’re having this argument.”

“About what?”

Protter got up, paced, glared again at his hands. He lumbered about, Ehrengraf thought, like a caged bear. His chino pants were ragged at the cuffs and his plaid shirt was a tartan no Highlander would recognize. Ehrengraf, in contrast, sparkled in the drab cell like a diamond on a dustheap. His suit was a herringbone tweed the color of a well-smoked briar pipe, and beneath it he wore a suede doeskin vest over a cream broadcloth shirt with French cuffs and a tab collar. His cufflinks were simple gold hexagons, his tie a wool knit in the same brown as his suit. His shoes were shell cordovan loafers, quite simple and elegant and polished to a high sheen.

“The argument,” Ehrengraf prompted.

“Oh, I don’t know how it got started,” Protter said. “One thing led to another, and pretty soon she’s making a federal case over me and this woman who lives one flight down from us.”

“What woman?”

“Her name’s Agnes Mullane. Gretchen’s giving me the business that me and Agnes got something going.”

“And were you having an affair with Agnes Mullane?”

Читать дальше