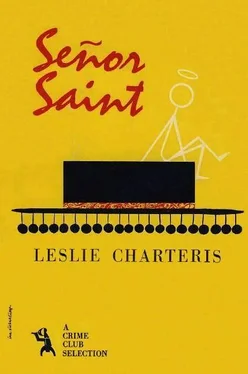

Leslie Charteris - Señor Saint

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - Señor Saint» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Garden City, New York, Год выпуска: 1958, Издательство: Crime Club by Doubleday, Жанр: Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Señor Saint

- Автор:

- Издательство:Crime Club by Doubleday

- Жанр:

- Год:1958

- Город:Garden City, New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Señor Saint: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Señor Saint»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

st st These four Latin-American adventures are “big enough” even for the Saint. They contain the ingredients which author Leslie Charteris

Señor Saint — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Señor Saint», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She clutched his arm, to make sure he would feel her shiver.

“No, it’s bad,” she said shakily. “They never play those drums for fun. Only for a blood ritual, a head chopping. I’ve heard them before — I can never forget...”

“Bad,” said the taciturn captain, in corroboration. “Muy malo!”

A single ear-splitting shriek pealed out of the blackness, hung quavering on a climax of agony, and was abruptly cut off.

“Oh, no,” Alice sobbed.

At the Saint’s first movement, she clung to him tighter.

“No, I won’t let you. There’s nothing you could do!”

Like a giant firefly, a torch blinked alight in the forest, flaring and eclipsing as it wandered among the trees. It was joined by another, and another, until there were six or seven of them shimmering and weaving towards the river, throwing weirdly moving silhouettes of deformed tree trunks and twisted jungle growth. The drums came nearer, picked up a more feverish tempo.

As the torches bobbed closer to the bank, they revealed not only the shapes of the brown men who carried them, but the gleaming leaping forms of a horde of other naked creatures that writhed and capered around them. The male population of the village where Loro sojourned didn’t do things by halves. He had explained to them that this was what the incomprehensible white tourists expected, and in return for the rum which he dispensed they were always ready to oblige. It was more fun for them than a square dance, anyway.

Then, as if at a signal, the torches drew together and became almost still. And in the midst of them, on the point of a spear, to an accompaniment of shrill yips and yells, was raised a bleeding human head.

This was Professor Humphrey Nestor’s crowning inspiration, the climactic triumph of his dramatic genius. The head, moulded in papier-mâché from a plaster matrix which the Professor had made himself, was a recognizable facsimile of Loro’s to pass at that distance and in the flickering torchlight, and the long black hair affixed to its scalp and the gold ring in one ear were clinchers of identification. The ketchup which dripped from its neck was a gruesome touch of realism which had become even more horrifyingly effective when some of the performers had discovered how good it tasted and had taken to dipping their fingers in the drips and licking them with ghoulish glee. Thus the subsidizer of the whole elaborate fraud was to be fully and incontrovertibly convinced that Loro was dead, the guns were lost, the expedition had failed, and there was nothing left but to kiss his investment goodbye and be thankful his own head was still on his shoulders. At that, he would go home with an anecdote to embroider for the rest of his life which in itself was almost worth the capital outlay, which he could take as a tax deduction, if he could get anyone to believe him.

Alice screamed.

All the torches went out as if a switch had been pulled. It had been found too dangerous to leave them alight any longer than it took to fulfil their purpose. One earlier victim had been so emotionally affected that he had fetched a gun and started blazing away, and might easily have hurt someone.

Out of the darkness that seemed to swallow the land again came a rustle like unseen wings, and a shower of arrows plonked into the bulkheads and the deck. They were shot by the best archers in the village, who could be relied on not to hit anyone accidentally.

The captain let out a yell of fear, and his machete flashed, cutting the bow rope by which they were moored with a single stroke. Instantly the boat started to move with the strong deep current. The captain scuttled into the wheelhouse, and as Simon instinctively dragged Alice down to the deck they heard the laboured grinding of the electric starter. The air quivered with bloodcurdling ululations from the Stygian shoreline. After four excruciating attempts the engine finally caught and the boat came under control, turning with increasing sureness out towards the centre of the river. Another shower of arrows fell mostly in the water behind them, and the hysterical war-whoops faded rapidly as the boat gathered speed with the stream.

Simon rose and helped Alice up, and sympathetically let her continue to hold on to him, since that was what she seemed to want.

“It’s all my fault,” she moaned. “I got Loro killed, and lost you all that money—”

“Loro got himself killed,” said the Saint sternly. “It was his own idea, and he was sure he could get away with it. Nobody was twisting his arm. As for the money, I don’t know what you think I’ve got to complain about.”

She had to force herself to recall how radically inappropriate half of her carefully rehearsed speech had become in the light of the veritable catastrophe which had intervened.

The boat, driving at full throttle down the stream which the climbing moon had turned into a floodlit highway, must already have been somewhere near the place which they had reached so laboriously that afternoon on foot. Simon pointed towards the now silent blackness of the land.

“I’m not an archaeologist, and I’ll be satisfied with what’s there,” he said. “I’ll be back with all the machinery necessary to get it out, and all the men that are needed — armed, if they have to be — to chase those head-hunters away. Before long, the head-hunters’ll probably have been scared so far off into the hills that you won’t have any trouble getting back into your frog cave. I’ll get along all right until then. I’ve still got that prospecting concession for this river — remember?”

5

“It was, literally, like an answer to prayer,” said Professor Humphrey Nestor piously. “As you know, Mr Tombs — I’m sure I must have mentioned it — I was scheduled to stop over to deliver a special lecture on Inca mythology at the University of Miami. So I had asked Michigan to forward my mail for a few days in care of the President. That is how I happened to receive this letter from the executors of this rich uncle from whom I frankly never expected to inherit so much as an old encyclopedia.”

He handed Simon the unfolded letter. It was nicely typed on a letterhead purporting to be that of a firm of New York attorneys, and informed Professor Humphrey Nestor that they were holding at his disposal a legacy of fifty thousand dollars from the estate of Hannibal Nestor, deceased, and would appreciate his instructions regarding delivery of the same.

Simon glanced at it and handed it back with a smile of congratulation. Nobody could esteem the value of an efficiently faked document higher than he.

“That’s simply wonderful,” he said whole-heartedly.

“Naturally,” said the Professor, “all I could think of was to get the money as quickly as possible and return here while we were still hot on the scent, as you might say, of those golden frogs.”

“Naturally.”

“Getting the money was only a matter of formality. Then I wired Alice, and took the next plane back here after my lecture. Of course, by that time you had already left on your ill-fated trip. No doubt you can imagine my feelings when she was forced to tell me the whole story. It would be impossible for me to forgive the bargain she made with you if I did not realize how altruistic although misguided her motives were. But both of us will always bear on our souls the burden of the death of poor faithful Loro.”

He bowed his head, and a subdued Alice, becomingly garbed in black, meekly followed suit.

“Don’t blame yourselves too much,” said the Saint. “I’ve already told her—”

The Professor raised his hand.

“Let us not discuss it,” he said. “All I ask, for my own satisfaction and peace of mind, is that you should permit me to reimburse you for your loss. Call it conscience money, or blood money, as you will. And let us consider that iniquitous compact ended, as if it had never been made.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Señor Saint»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Señor Saint» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Señor Saint» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.