Alistair MacLean

FEAR IS THE KEY

1961

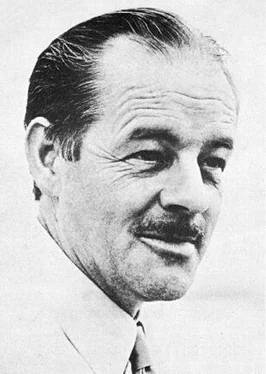

The Second World War changed everything, including how authors became authors. Case in point: a boy was born in Scotland, in 1922, and raised in Daviot, which was a tiny village southeast of Inverness, near the remote northern tip of the British mainland, closer to Oslo in Norway than London in England. In the 1920s and 30s such settlements almost certainly had no electricity or running water. They were not reached by the infant BBC’s wireless service. The boy had three brothers, but otherwise saw no one except a handful of neighbors. Adding to his isolation, his father was a minister in the Church of Scotland, and the family spoke only Gaelic at home, until the boy was six, when he started to learn English as a second language. Historical precedent suggested such a boy would go on to live his whole life within a ten-mile radius, perhaps working a rural white-collar job, perhaps as a land agent or country solicitor. Eventually the BBC’s long-wave Home Service would have become scratchily audible, and ghostly black and white television would have arrived decades later, when the boy was already middle aged. Such would have been his life.

But Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, and the isolated boy turned 18 in 1940, and joined the Royal Navy in 1941. Immediately he was plunged into the company of random strangers from all over the British Isles and the world, all locked cheek-by-jowl together in a desperate rough-and-tumble bid for survival and victory. He saw deadly danger in the North Atlantic and on Arctic convoys, including the famous PQ 17, and in the Mediterranean, and in the Far East, where ultimately his combat role was pre-empted by the atom bombs and the Japanese surrender, no doubt to his great relief, but where he saw horrors of a different kind, ferrying home the sick and skeletal survivors of Japanese prison camps. Like millions of others, the boy came out of this five-year crucible a 24-year-old man, his horizons radically expanded, his experiences increased many thousandfold, and like many of the demobilized, his nature perturbed by an inchoate restlessness, and his future dependent on a vague, unasked question: well, now what?

The man was Alistair MacLean, and he became a schoolteacher. But the restlessness nagged at him. He wanted more. He began writing short stories, and in 1954, the year I was born, he won a newspaper competition. Legend has it the prize was a hundred pounds, which if true was an enormous sum of money – half of what my dad earned that year, as a junior but determinedly white-collar civil servant. The story was a maritime tale. The competition win was followed by a commission from the Glasgow publisher Collins, to write a novel, with a thousand-pound advance – another enormous sum. That novel was HMS Ulysses, which drew on MacLean’s own experiences on the Murmansk convoys. It was an immediate and significant success. It was followed by The Guns of Navarone and South by Java Head , both also set during the war, and both also huge sellers. After three books MacLean was comfortably established as one of the world’s biggest-selling fiction writers.

His next three books were different, in one important way – they were set postwar. In the first half of the 1950s, British popular culture was utterly dominated by war stories, very understandably, given the depths of the recent dangers and the immensity of the recent triumph. Churchill was prime minister again. On the page and the screen, brave pilots bombed from low levels, and plucky POWs escaped through sandy tunnels, and charging destroyers smashed through towering waves. The first movie I ever saw was The Dam Busters . The second was Reach for the Sky . A Saturday morning double bill, up at Villa Cross, for ninepence. Comic books were full of lantern-jawed privates, fighting through Normandy.

But it had to stop. At some point we had to move on. Merely a question of timing. It was a fraught decision. A delicate psychological balance. The Suez crisis of 1956 was a humiliation that rubbed our noses in our much-diminished power and status. The temptation to keep on revisiting past glories was huge. But the present was happening, and the future was almost upon us. MacLean adapted better than most, perhaps because – as his books show – he was notably non-ideological. He wasn’t a Colonel Blimp, living in the past. He had a healthy cynicism about the present, and no great hopes for the future. He had no political position. As a result he was able to nimbly unmoor himself from 1939–1945 in narrative terms, but crucially he was smart enough to bring with him the tropes and memes he had developed while writing about those years. The result was his second trio of novels, books four, five and six, which I think surely represent the absolute plateau of his talent and achievement. They are the perfect MacLeans. Some will argue that the hot streak continued another five years (the Ian Stuart pen name being then unknown) and I would agree that book seven, The Golden Rendezvous , and book nine, When Eight Bells Toll , are almost-perfect MacLeans, glorious and solid in every possible way, but, in my view, slightly backward-looking, slightly over-reliant on muscle memory, not quite able to overcome the Perfect Three’s gravitational pull.

The first of the Perfect Three was MacLean’s fourth novel, The Last Frontier . Its backstory was rooted in wartime events, and its characters were war-weary and war-experienced, but its setting was explicitly contemporary late-1950s, in communist Hungary, with the recent uprising still fresh in the memory. True to Maclean’s non-ideological nature, the book contains an astonishingly humane and sympathetic understanding of Soviet feelings and paranoia. Its characters are compelling and multi-dimensional, and in some cases genuinely and affectingly tragic. By any standard it’s one of the great postwar thrillers.

Next up was Night Without End . It’s set when commercial transatlantic air travel was just beginning to change from a pipe dream to a roaring, thrashing reality. In terms of structure, it’s a classic locked-room mystery, but set on the polar icecap. An airliner crashes near a remote research station. The scientists rescue the survivors. One of them is clearly a murderer. Various clocks start ticking. It firms up MacLean’s instinctive facility with character types. He knew what we wanted from the hero. He knew we wanted a talented and uncompromising sidekick. Overall it’s a total success. Weather has never been done better.

The last of the Perfect Three is Fear is the Key , the volume you’re holding right now. It has everything. Its melancholy opening harks back to those millions of unspoken demob questions: what now? Some young veterans knew they could never settle down, nine to five. They started cockamamie charter airlines, or rag-tag air cargo operations, using war-surplus planes. John Talbot – this book’s hero and first-person narrator – did just that, in partnership with his brother. It didn’t end well. Read on, to find out how justice is served. Along the way you’ll enjoy every single one of MacLean’s signature strengths, all present and correct and in perfect working order – the silent but preternaturally skilled boatman, the stolid and reliable family chauffeur, who we know will play a minor role in saving the day, the dramatic physical infrastructure, the constant presence of the sea, its sound and smell, its depths and dangers. Plus an opening with an amazing first reveal. Above all you’ll enjoy the easy and natural grip of a born storyteller. It feels like coming back to a place you had a good time before.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу