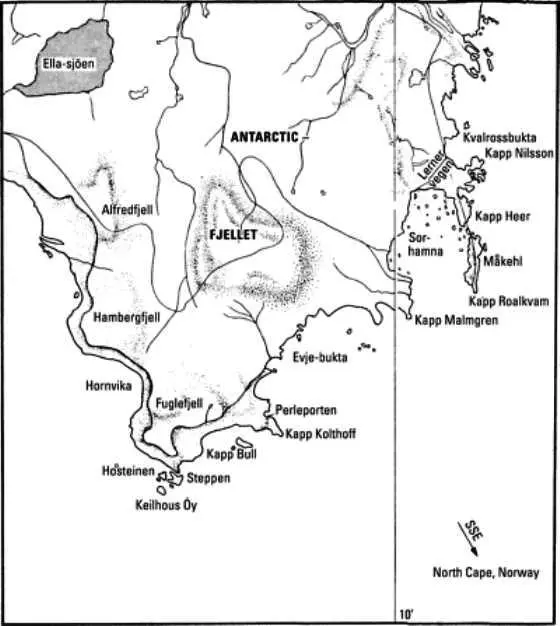

It took me just on an hour and a half to cover less than a mile and arrive at a vantage point of a height of about five hundred feet that enabled me to see into the next bay – the Evjebukta. This wide U-shaped bay, stretching from Kapp Malmgren in the north-east to Kapp Kolthoff in the south-west, was just over a mile in length and perhaps half of that in width: the entire coastline of the bay consisted of vertical cliffs, a bleak, forbidding and repellent stretch of grey water and precipitous limestone that offered no haven to those in peril on the sea.

I stretched out gratefully on the snow and, when the thumping of my heart and the rasping of my breathing had quietened sufficiently for me to hold a pair of binoculars steady, I used them to quarter the Evjebukta. It was completely bereft of life. The sun was up now, low over the southeastern horizon, but even although it was in my eyes, visibility was good enough and the resolution of the binoculars such that I could have picked up a sea-gull floating on the waters. There were some little islands to the north of the bay and, of course, there were the cliffs immediately below me that blocked off all view of what might be happening at their feet: but if the boat was concealed either behind an island or under the cliffs, it was most unlikely that Heissman would remain in such positions long for there would be nothing to detain him.

I looked south beyond the tip of Kapp Kolthoff and there, beyond the protection of the headland, the sun glinted off the broken tops of white water. I was as certain as one could be without absolute proof that they would not have ventured beyond the protection of the point: Heissman’s unseamanlike qualities apart, Goin was far too prudent a man to step unheedingly into anything that would even smack of danger.

How long I lay there waiting for the boat to appear either from behind an island or out from under the concealment of the nearest cliffs I didn’t know: what I did know was that I suddenly became aware of the fact that I was shaking with the cold and that both hands and feet were almost completely benumbed. And I became aware of something else. For several minutes now I’d had the binoculars trained not on the north end of the bay but at the foot of the cliffs to the south on a spot where, about three hundred yards north-west of the tip of Kapp Kolthoff, there was a peculiar indentation in the cliff walls. Partly because of the fact that it appeared to bear to the right and out of sight behind one of the cliff-faces guarding the entrance, and partly because, due to the height of the cliffs and the fact that the sun was almost directly behind, the shadows cast were very deep, I was unable to make out any details beyond this narrow entrance. But that it was an entrance to some cove beyond I didn’t doubt. Of any place within the reach of my binoculars it was the only one where the boat could have lain concealed: why anyone should wish to lie there at all was another matter altogether, a reason for which I couldn’t even guess at. One thing was for certain, a landward investigation from where I lay was out of the question: even if I didn’t break my neck in the minimum of the two-hour journey it would take me to get there, nothing would be achieved by making such a trip anyway, for not only did the descent of those beetling black cliffs seem quite suicidal but, even if it were impossibly accomplished, what lay at the end of it removed any uncertainty about the permanency of the awaiting reception: for there was no foreshore whatever, just the precipitous plunge of those limestone walls into the dark and icy seas.

Stiffly, clumsily, I rose and headed back towards the cabin. The trip back was easier than the outwards one for it was downhill, and by following my own tracks I was able to avoid most of the involuntary descents into the sunken snow-drifts that had punctuated my climb. Even so, it was nearer one o’clock than noon when I approached the cabin.

I was only a few paces distant when the main door opened and Mary Stuart appeared. One look at her and my heart turned over and something cold and leaden seemed to settle in the pit of my stomach. Dishevelled hair, a white and shocked face, eyes wild and full of fear, I’d have had to be blind not to know that somewhere, close, death had walked by again.

‘Thank God!’ Her voice was husky and full of tears. ‘Thank God you’re here! Please come quickly. Something terrible has happened.’

I didn’t waste time asking her what, clearly I’d find out soon enough, just followed her running footsteps into the cabin and along the passage to Judith Haynes’s opened door. Something terrible had indeed happened, but there had been no need for haste. Judith Haynes had fallen from her cot and was lying sideways on the floor, half-covered by her blanket which she’d apparently dragged down along with her. On the bed lay an opened and three parts empty bottle of barbiturate tablets, a few scattered over the bed: on the floor, its neck still clutched in her hand, lay a bottle of gin, also three-parts empty. I stooped and touched the marble forehead: even allowing for the icy atmosphere in the cubicle, she must have been dead for hours. Make it a long sleep, she’d said to me: make it a long sleep.

‘Is she – is she–?’ The dead make people speak in whispers.

‘Can’t you tell a dead person when you see one?’ It was brutal of me but I felt flooding into me that cold anger that was to remain with me until we’d left the island.

‘I – I didn’t touch her. I–’

‘When did you find her?’

‘A minute ago. Two. I’d just made some food and coffee and I came to see–’

‘Where are the others? Lonnie, Sandy, Eddie?’

‘Where are – I don’t know. They left a little while ago – said they were going for a walk.’

A likely tale. There was only one reason that would make at least two of the three walk as far as the front door. I said: ‘Get them. You’ll find them in the provisions shed.’

‘Provisions shed? Why would they be there?’

‘Because that’s where Otto keeps his scotch.’

She left. I put the gin bottle and barbiturate bottle to one side, then I lifted Judith Haynes on to the bed for no better reason than that it seemed cruel to leave her lying on the wooden floor. I looked quickly around the cubicle, but I could see nothing that could be regarded as untoward or amiss. The window was still screwed in its closed position, the few clothes that she had unpacked neatly folded on a small chair. My eye kept returning to the gin bottle. Stryker had told me and I’d overheard her telling Lonnie that she never drank, had not drunk alcohol for many years: an abstainer does not habitually carry around a bottle of gin just on the off-chance that he or she may just suddenly feel thirsty.

Lonnie, Eddie and Sandy came in, trailing with them the redolence of a Highland distillery, but that was the only evidence of their sojourn in the provision shed; whatever they’d been like when Mary had found them, they were shocked cold sober now. They just stood there, staring at the dead woman and saying nothing: understandably, I suppose, they thought there was nothing they could usefully say.

I said: ‘Mr Gerran must be informed that his daughter is dead. He’s gone north to the next bay. He’ll be easy to find – you’ve only got to follow the Sno-Cat’s tracks. I think you should go together.’

‘God love us all.’ Lonnie spoke in a hushed and anguished reverence. ‘The poor girl. The poor, poor lassie. First her man – and now this. Where’s it all going to end, Doctor?’

‘I don’t know, Lonnie. Life’s not always so kind, is it? No need to kill yourselves looking for Mr Gerran. A heart attack on top of this we can do without.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу