‘All seems perfectly straightforward. You do seem to have this organized. You know, I’m beginning to think that the Government regard Van Diemen’s pieces of paper as very valuable indeed.’

‘One gathers that impression. By the way, I’m curious. How long does your memory span last?’

‘As long as I want.’

‘So you’ll be able to memorize the contents of those papers and reproduce them, say, a year later?’

‘I should think so.’

‘Let’s hope that’s the way it’s going to be – that you’re going to be given the chance to reproduce them, I mean. Let’s hope nobody ever finds out that you got in there, did your mentalist bit and left unseen. Let’s hope, in other words, that you don’t have to use these.’ From the breast pocket of his jacket Harper unclipped a couple of pens, one black, one red. They were of the heavy felt-Biro type with the release button at the top. ‘I picked these up in town today. I don’t have to tell you where I picked them up.’

Bruno looked at the pens, then at Harper. ‘What on earth would I want to use those things for?’

‘Whatever the faults of our science and research department, it’s not lack of imagination. They positively dote on dreaming up these little toys. You don’t think I’m going to let you cross two eastern frontiers with a couple of Peacemaker Colts strapped to your waist? These are guns. Yes, guns. The red one is the nasty one, the one with the anaesthetic-tipped needles which are not so healthy for those with heart conditions; the other one is the gas gun.’

‘So small?’

‘With the micro-miniaturization techniques available today, those are positively bulky. The needle gun has an effective range of forty feet, the gas gun of not more than four. Operation is simplicity itself. Depress the button at the top and the gun is armed: press the pocket clip and the gun is fired. Stick them in your outside pocket. Let people get used to the sight of them. Now listen carefully while I outline the plans for Crau.’

‘But I thought you had already agreed to the plan – my plan.’

‘I did and I do. This is merely a refinement of the original part of that plan. You may have wondered why the CIA elected to send you with a medical person. When I have finished you will understand.’

Some four hundred and fifty miles to the north, three men sat in a brightly lit, windowless and very austere room, the furniture of which consisted mainly of metal filing cabinets, a metal table and some metal-framed chairs. All three were dressed in uniform. From the insignia they wore, one was a colonel, the second a captain, the third a sergeant. The first was Colonel Serge Sergius, a thin, hawk-faced man with seemingly lidless eyes and a gash where his mouth should have been: his looks perfectly befitted his occupation, which was that of a very important functionary in the secret police. The second, Captain Kodes, was his assistant, a well-built athletic man in his early thirties, with a smiling face and cold blue eyes. The third, Sergeant Angelo, was remarkable for one thing only, but that one thing was remarkable enough. At six feet three, Angelo was considerably too broad for his height, a massively muscular man who could not have weighed less than two hundred and fifty pounds. Angelo had one function and one only in life – he was Sergius’s personal bodyguard. No one could have accused Sergius of choosing without due care and attention.

On the table a tape recorder was running. A voice said: ‘and that is all we have for the moment’. Kodes leaned forward and switched off the recorder.

Sergius said: ‘And quite enough. All the information we want. Four different voices. I assume, my dear Kodes, that if you were to meet the owners of those four voices you could identify them immediately?’

‘Without the shadow of a doubt, sir.’

‘And you, Angelo?’

‘No question, sir.’ Angelo’s gravelly booming voice appeared to originate from the soles of his enormous boots.

‘Then please go ahead, Captain, with the reservation of our usual rooms in the capital – the three of us and the cameraman. Have you chosen him yet, Kodes?’

‘I thought young Nicolas, sir. Extraordinarily able.’

‘Your choice.’ Colonel Sergius’s lipless mouth parted about a quarter of an inch, which meant that he was smiling. ‘Haven’t been to the circus for thirty years – circuses had ceased to exist during the war – but I must say I’m looking forward with almost childish enthusiasm to this one. Especially one which is as highly spoken of as this one is. Incidentally, Angelo, there is a performer in this circus whom I’m sure you will be most interested to see, if not meet.’

‘I do not care to see or meet anyone from an American circus, sir.’

‘Come, come, Angelo, one must not be so chauvinistic.’

‘Chauvinistic, Colonel?’

Sergius made to explain then decided against the effort. Angelo was possessed of many attributes but a razor-sharp intelligence was not among them.

‘There are no nationalities in a circus, Angelo, only artistes, performers: the audience does not care whether the man on the trapeze comes from Russia or the Sudan. The man I refer to is called Kan Dahn and they say that he is even bigger than you. He is billed as the strongest man in the world.’

Angelo made no reply, merely inflated his enormous chest to its maximum fifty-two inches and contented himself with a smile of wolfish disbelief.

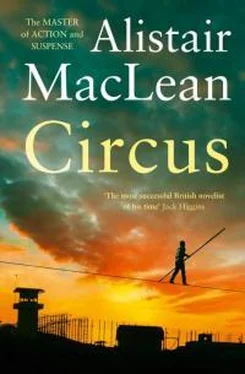

The three-day stay in Austria was by now the inevitable enormous success. From there the circus moved north and, after only one stop-over, arrived in the city where Sergius and his subordinates had moved to meet them.

At the evening performance, those four had taken the best seats about six rows back facing the centre of the centre ring. All four were in civilian clothes and all four were unmistakably soldiers in civilian clothes. One of them, immediately after the beginning of the performance, produced a very expensive-looking camera with a telephoto lens, and the sight of this produced a senior uniformed police officer in very short order indeed. The taking of photographs was officially discouraged, while with Westerners the illegal possession of an undeclared camera, if discovered, was a guarantee of arrest and trial: every camera aboard the circus train had been impounded on entering the country and would not be returned until the exit frontier had been crossed.

The policeman said: ‘The camera please: and your papers.’

‘Officer.’ The policeman turned towards Sergius and gave him the benefit of his cold insolent policeman’s stare, a stare that lasted for almost a full second before he swallowed what was obviously a painful lump in his throat. He moved in front of Sergius and spoke softly: ‘Your pardon, Colonel. I was not notified.’

‘Your headquarters were informed. Find the incompetent and punish him.’

‘Sir. My apologies for–’

‘You’re blocking my view.’

And, indeed, the view was something not to be blocked. No doubt inspired by the fact that they were being watched by connoisseurs, and wildly enthusiastic connoisseurs at that, the company had in recent weeks gone from strength to strength, honing and refining and polishing their acts, continually inventing more difficult and daring feats until they had arrived at a now almost impossible level of perfection. Even Sergius, who was normally possessed of a mind like a refrigerated computer, gave himself up entirely to the fairyland that was the circus. Only Nicolas, the young – and very presentable – photographer, had his mind on other things, taking an almost non-stop series of photographs of all the main artistes in the circus. But even he forgot his camera and his assignment as he stared – as did his companions – in total disbelief as The Blind Eagles went through their suicidal aerial routine.

Читать дальше