Summer found a towel and hurried over to Trevor, who was compressing the cut on his shoulder as he stared blankly at the ruins of his boat. As a police siren wailed its imminent approach, Trevor turned and gazed at Summer with a look of hurt and anger.

“It has to be Terra Green,” he muttered quietly. “I wonder if they killed my brother, too?”

* * *

At a harborside coffee shop two miles away, Clay Zak stared out the window, admiring the plume of smoke and flame that rose above the water in the distance. Finishing an espresso and Danish, he left a large tip on the table, then walked to his brown rented Jeep parked up the street.

“Smoke on the water,” he muttered aloud, humming the Deep Purple rock tune before climbing into the car. Without the least concern, he drove to the airport outside of town, where Mitchell Goyette’s private jet waited for him on the tarmac.

The business jet circled the airfield once, waiting for a small plane to take off and clear the field, before the control tower gave approval to land. Painted in the same shade of turquoise as its fellow sea vessels, the NUMA Hawker 750 touched down lightly on the runway. The small jet taxied to a redbrick building before pulling to a halt alongside a much larger Gulfstream G650. The fuselage door opened and Pitt quickly stepped out, slipping on a jacket to ward off a brisk chill in the air. He walked into the terminal building, where he was greeted by a rotund man standing behind a counter.

“Welcome to Elliot Lake. It’s not often we have two jets in on the same day,” he said in a friendly rural voice.

“A little short for the carriers?” Pitt asked.

“Our runway is only forty-five hundred feet, but we hope to expand it next year. Can I fix you up with a rental car?”

Pitt nodded, and soon left the terminal with a set of keys to a blue Ford SUV. Spreading a map on the hood of the car, he studied his new surroundings. Elliot Lake was a small town near the northeast shores of Lake Huron. Situated some two hundred and seventy-five miles due north of Detroit, the town lay in the Algoma District of Ontario Province. Surrounded by Canadian wilderness, the landscape was a lush mix of rugged mountains, winding rivers, and deep lakes. Pitt found the airport on his map, carved out of the dense forest a few miles south of the town. He traced a lone highway that traveled south through the mountains, culminating on the shores of Lake Huron and the Trans-Canada Highway. About fifteen miles to the west was Pitt’s destination, an old logging and mining town called Blind River.

The drive was scenic, the road winding past several mountain lakes and a surging river that dropped over a steep waterfall. The terrain flattened as he reached the shores of Lake Huron and the town of Blind River. He drove slowly through the small hamlet, admiring the quaint wooden homes, which were mostly built in the 1930s. Pitt continued past the city limits until he spotted a large steel warehouse adjacent to a field littered with high mounds of rock and ore. A large maple leaf flag flew above a weathered sign that read ONTARIO MINERS CO-OP AND REPOSITORY. Pitt turned in and parked near the entrance as a broad-shouldered man in a brown suit walked down the steps and climbed into a late-model white sedan. Pitt noticed the man staring at him through a pair of dark sunglasses as he climbed out of his own rental car and entered the building.

The dusty interior resembled a mining museum. Rusty ore carts and pickaxes jammed the corners, alongside high shelves that overflowed with mining journals and old photographs. Behind a long wooden counter sat a massive antique banker’s safe that Pitt guessed held the more valuable mineral samples.

Seated behind the counter was an older man who appeared almost as dusty as the room’s interior. He had a bulb-shaped head, and his gray hair, eyes, and mustache matched the faded flannel shirt he wore beneath a pair of striped suspenders. He peered at Pitt through a pair of Ben Franklin glasses perched low on his nose.

“Good morning,” Pitt said, introducing himself. Gazing up at a polished tin container that resembled a large liquor flask, he remarked, “Beautiful old oil cadger you have there.”

The old man’s eyes lit up as he realized Pitt wasn’t a lost tourist looking for directions.

“Yep, used to refill the early miners’ oil lamps. Came from the nearby Bruce Mines. My grandpappy worked the copper mines there till they shut down in 1921,” he said in a wheezy voice.

“A lot of copper in these hills?” Pitt asked.

“Not enough to last long. Most of the copper and gold mines shut down decades ago. Attracted a lot of dirt diggers in their day, but not too many folks got rich from it,” he replied, shaking his head. Looking Pitt in the eye, he asked, “What can I do for you today?”

“I’d like to know about your stock of ruthenium.”

“Ruthenium?” he asked, looking at Pitt queerly. “You with that big fellow that was just in here?”

“No,” Pitt replied. He recalled the odd behavior of the man in the brown suit and tried to shake off a nagging sense of familiarity.

“That’s peculiar,” the man said, eyeing Pitt with suspicion. “That other fellow was from the Natural Resources Ministry in Ottawa. Here checking our supply and sources of ruthenium. Odd that it was the only mineral he was interested in and you come walking in asking about the same thing.”

“Did he tell you his name?”

“John Booth, I believe he said. A bit of an odd bird, I thought. Now, what’s your interest, Mr. Pitt?”

Pitt generally explained Lisa Lane’s research at George Washington University and ruthenium’s role in her scientific work. He neglected to disclose the magnitude of her recent discovery or the recent explosion at the lab.

“Yes, I recall sending a sample to that lab a week or two ago. We don’t get too many requests for ruthenium, just a few public research labs and the occasional high-tech company. With the price going so crazy, not too many folks can afford to dabble with it anymore. Of course, that price spike has made us a nice profit when we do get an order,” he smiled with a wink. “I just wish we had a source to replenish our inventory.”

“You don’t have an ongoing supplier?”

“Oh heavens no, not in years. I reckon my stock will be depleted before long. We used to get some from a platinum mine in eastern Ontario, but the ore they are pulling out now isn’t showing any meaningful content. No, as I was telling Mr. Booth, most of our ruthenium stocks came from the Inuit.”

“They mined it up north?” Pitt asked.

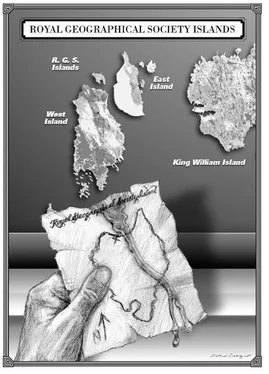

“Apparently so. I pulled the acquisition records for Mr. Booth,” he said, pointing to an ancient leather-bound journal sitting at the other end of the counter. “The stuff was acquired over a hundred years ago. There’s a detailed accounting in the logbook. The Inuit referred to it as the ‘Black Kobluna’ or some such. We always called it the Adelaide sample, as the Inuit were from a camp on the Adelaide Peninsula in the Arctic.”

“So that’s the extent of the Canadian supply of ruthenium?”

“As far as I know. But nobody knows if there is more to the Inuit source. It all surfaced so long ago. The story was that the Inuit were afraid to return to the island where they obtained it because of a dark curse. Something about bad spirits and the source being tainted by death and insanity, or similar mumbo jumbo. A tall tale of the north, I guess.”

“I’ve found that local legends often have some basis in fact,” Pitt replied. “Do you mind if I take a look at the journal?”

“Not at all.” The old geologist ambled down to the end of the counter and returned with the book, flipping through its pages as he walked. A scowl suddenly crossed his face as his skin turned beet red.

Читать дальше