“Hello, Miss Goodyear,” he said, springing up from the desk. “I received your message that you would be coming by this morning.”

“You’re looking well, Aldrich. Keeping the manor full?”

“Business is quite nice, thank you. Had a couple of short-term visitors check in already today.”

“This is my friend Summer Pitt, who’s helping me with my research.”

“Nice to meet you, Miss Pitt,” he said, extending a hand. “You probably want to get right to work, so why don’t you follow me on back?”

He led them through a side door into a private wing that encompassed his own living quarters. They walked through a large sitting area filled with artifacts from North Africa and the Middle East, all acquired by Kitchener during his Army years stationed in the region. Aldrich then opened another door and ushered them into a wood-paneled study. Summer noticed that one entire wall was lined with tall mahogany filing cabinets.

“I would have thought you’d have all of Uncle Herbert’s files memorized by now,” Aldrich said to Julie with a smile.

“I’ve certainly spent enough time with them,” Julie agreed. “We just need to review some of his personal correspondence in the months preceding his death.”

“Those will be in the last cabinet on the right.” He turned and walked toward the doorway. “I’ll be at the front desk, should you require any assistance.”

“Thank you, Aldrich.”

The two women quickly dove into the file cabinet. Summer was glad to see the correspondence was of a more personal and interesting nature than the records at the Imperial War Museum. She slowly read through dozens of letters from Kitchener’s relatives, along with what seemed an endless trail of correspondence from building contractors, who were being cajoled and pushed by Kitchener to complete refurbishments on Broome Park.

“Look how cute this is,” she said, holding up a card of a hand-drawn butterfly sent from Kitchener’s three-year-old niece.

“The gruff old general was quite close with his sister and brothers and their children,” Julie said.

“Looking at an individual’s personal correspondence is a great way to get to know him, isn’t it?” Summer said.

“It really is. A shame that the handwritten letter has become a lost art form in the age of e-mail.”

They searched for nearly two hours before Julie sat up in her chair.

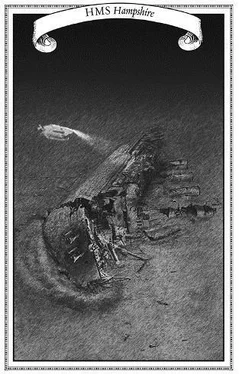

“My word, it didn’t go down on the Hampshire ,” she blurted.

“What are you talking about?”

“His diary,” Julie replied with wide eyes. “Here, take a look at this.”

It was a letter from an Army sergeant named Wingate, dated a few days before the Hampshire was sunk. Summer read with interest how the sergeant expressed his regret at being unable to accompany Kitchener on his pending voyage and wished the field marshal well on his important trip. It was a brief postscript at the bottom of the page that made her stiffen.

“‘P.S. Received your diary. Will keep it safe till your return,’” she read aloud.

“How could I have missed it?” Julie lamented.

“It’s an otherwise innocuous letter, written in very messy handwriting,” Summer said. “I would have skimmed past it, too. But it’s a wonderful discovery. How exciting, his last diary may indeed still exist.”

“But it’s not here or in the official records. What was that soldier’s name again?”

“Sergeant Norman Wingate.”

“I know that name but can’t place it,” Julie replied, racking her brain.

A high-pitched squeak echoed from the other room, slowly growing louder in intensity. They looked to the doorway to see Aldrich entering the study pushing a tea cart with a bad wheel.

“Pardon the interruption, but I thought you might enjoy a tea break,” he said, pouring cups for each of them.

“That’s very kind of you, Mr. Kitchener,” Summer said, taking one of the hot cups.

“Aldrich, do you happen to recall an acquaintance of Lord Kitchener by the name of Norman Wingate?” Julie asked.

Aldrich rubbed his brow as his eyes darted toward the ceiling in thought.

“Wasn’t he one of Uncle Herbert’s bodyguards?” he asked.

“That’s it,” Julie said, suddenly remembering. “Wingate and Stearns were his two armed guards approved by the Prime Minister.”

“Yes,” Aldrich said. “The other fellow… Stearns, you say his name was? He went down on the Hampshire with Uncle Herbert. But Wingate didn’t. He was sick, I believe, and didn’t make the trip. I recall my father often lunching with him many years later. The chap apparently suffered a bit of guilt for surviving the incident.”

“Wingate wrote that he had the field marshal’s last diary in his possession. Do you know if he gave it to your father?”

“No, that would have been here with the rest of his papers, I’m certain. Wingate probably kept it as a memento of the old man.”

A faint buzzer sounded from the opposite end of the house. “Well, someone is at the front desk. Enjoy the tea,” he said, then shuffled out of the study.

Summer reread the letter then examined the return address.

“Wingate wrote this from Dover,” she said. “Isn’t that just down the road?”

“Yes, less than ten miles,” Julie replied.

“Maybe Norman has some relatives in the city that might know something.”

“Might be a long shot, but I suppose it’s worth a try.”

With the aid of Aldrich’s computer and a Kent Regional Phone Directory, the women assembled a list of all the Wingates living in the area. They then took turns phoning each name, hoping to locate a descendant of Norman Wingate.

The phone queries, however, produced no leads. After an hour, Summer hung up and crossed out the last name on the list with a shake of her head.

“Over twenty listings and not even a hint,” she said with disappointment.

“The closest I had was a fellow who thought Norman might have been a great-uncle, but he had nothing else to offer,” Julie replied. She looked down at her watch.

“I suppose we should go check into our hotel. We can finish the files in the morning.”

“We’re not staying at Broome Park?”

“I booked us in a hotel in Canterbury, near the cathedral. I thought you’d want to see it. Besides,” she said, her voice dropping to a whisper, “the food here isn’t very good.”

Summer laughed, then stood and stretched her arms. “I won’t tell Aldrich. I’m wondering if we might be able to make one stop along the way first.”

“Where would that be?” Julie asked with a quizzical look.

Summer picked up the letter from Wingate and read the return address. “Fourteen Dorchester Lane, Dover,” she said with a wry smile.

* * *

The motorcyclist slipped on a black helmet with matching visor, then peeked around the back end of a gardener’s truck. He patiently waited as Julie and Summer stepped out the front door of Broome Park. Careful not to let himself be seen, he watched as they climbed into their car across the parking lot and then drove down the road to the exit. Starting his black Kawasaki motorcycle, he eased toward the lane, keeping a wide buffer between himself and the departing car. Watching Julie turn toward Dover, he let a few cars pass, then followed suit, keeping the little green car just ahead in his sights.

Modern Dover is a bustling port city best known for its ferry to Calais and its world-famous white chalk cliffs up the easterly coastline. Julie drove into the historic city center before pulling over and asking for directions. They found Dorchester Lane a few blocks from the waterfront, a quiet residential street lined with old brick row houses constructed in the 1880s. Parking the car under a towering birch tree, the women walked up the cleanly swept steps of number fourteen and rang the bell. After a long pause, the door was pulled open by a disheveled woman in her twenties who held a sleeping baby in her arms.

Читать дальше