Julie Goodyear strolled past a monstrous pair of long-silenced fifteen-inch naval guns pointed toward the Thames, then walked up the steps to the entrance of the Imperial War Museum. The venerated national institution in the London borough of Southwark was housed in a nineteenth-century brick edifice originally constructed as a hospital for the mentally ill. Known for its extensive collection of photographs, art, and military artifacts from World Wars I and II, the museum also contained a large archive of war documents and private letters.

Julie checked in at the information desk in the main atrium, where she was escorted up two floors in a phone-booth-sized elevator, then climbed an additional flight of stairs until reaching her destination. The museum’s reading room was an impressive circular library constructed in the building’s high central dome.

A bookish woman in a brown dress smiled in recognition as she approached the help desk.

“Good morning, Miss Goodyear. Back for another visit with Lord Kitchener?” she asked.

“Hello again, Beatrice. Yes, I’m afraid the field marshal’s enduring mysteries have drawn me back once more. I phoned a few days ago with a request for some specific materials.”

“Let me see if they have been pulled,” Beatrice replied, retreating into the private archives depository. She returned a minute later with a thick stack of files under her arm.

“I have an Admiralty White Paper inquiry on the sinking of the HMS Hampshire and First Earl Kitchener’s official war correspondence in the year 1916,” the librarian said as she had Julie sign out the documents. “Your request appears to be complete.”

“Thanks, Beatrice. I should just be a short while.”

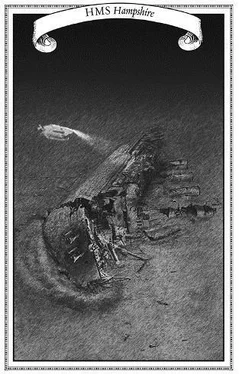

Julie took the documents to a quiet corner table and began reading the Admiralty report on the Hampshire . There was little information to be had. She had seen earlier accusations against the Royal Navy by residents of the Orkneys, who claimed the Navy dithered in sending help to the stricken ship after its loss had been reported. The official report clearly covered up any wrongdoings by the Navy and brushed aside rumors that the ship sank by means other than a mine.

Kitchener’s correspondence proved only slightly more illuminating. She had read his war correspondence before and had found it mostly mundane. Kitchener held the post of Secretary of State for War in 1916, and most of his official writings reflected his preoccupation with manpower and recruiting needs of the British Army. A typical letter complained to the Prime Minister about pulling men from the Army to work in munition factories on the home front.

Julie skimmed rapidly through the pages until nearing June fifth, the date of Kitchener’s death on the Hampshire . The discovery that the Hampshire had sunk from an internal explosion compelled her to consider the possibility that someone may have actually wanted him dead. The notion led her to an odd letter that she had seen months before. Thumbing through the bottom of the file, her fingers suddenly froze on the document.

Unlike the aged yellowing military correspondence, this letter was still bright white, typed on heavy cotton paper. At the top of the page was embossed “Lambeth Palace.” Slowly, Julie read the letter.

Sir,

At behest of God and Country, I implore you a final time to relinquish the document. The very sanctity of our Church depends upon it. For while you may be waging a temporal war with the enemies of England, we are waging an eternal crusade for the salvation of all mankind. Our enemies are wicked and cunning. Should they seize the Manifest, it could spell the demise of our very faith. I strongly submit there is no choice but for you to accede to the Church. I await your submittal,

— Randall Davidson

Julie recognized the author as the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the margins, she noticed a handwritten notation that said “Never!” It was written in a script that she recognized as Kitchener’s.

The letter struck her as perplexing on several levels. Kitchener, she knew, had been a churchgoing religious man. Her research had never revealed any conflicts with the Church of England, let alone the head of the Church himself, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Then there was the reference to the document or Manifest. What could that possibly be?

Though the letter seemed to have no possible bearing on the Hampshire , it was intriguing enough to stir her interest. She made a photocopy of the letter, then worked her way through the rest of the folder. Near the bottom, she found several documents related to Kitchener’s trip to Russia, including a formal invitation from the Russian Consulate and an itinerary while in Petrograd. She copied these as well, then returned the folder to Beatrice.

“Find what you were looking for?” the librarian asked.

“No, just an odd kernel here and there.”

“I’ve found that the key to discovering historical treasures is to just keep on kicking over the stones. Eventually, you’ll get there.”

“Thank you for your assistance, Beatrice.”

As she left the museum and made her way to her car, Julie reread the letter several times, finally staring at the Archbishop’s signature.

“Beatrice is right,” she finally muttered to herself. “I need to kick over some more stones.”

She didn’t have far to go. Barely a half mile down the road sat historic Lambeth Palace. A collection of ancient brick buildings towering over the banks of the Thames River, it served as the historical London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Of particular interest to Julie was the presence on the grounds of the Lambeth Palace Library.

Julie knew that the palace was not typically open to the public, so she parked on a nearby street and walked to the main gate. Passing a security checkpoint, she was allowed to proceed to the Great Hall, a Gothic-style red brick building accented with white trim. Contained inside the historic structure was one of the oldest libraries in Britain, and the principal repository for the Church of England’s archives, dating back to the ninth century.

She stepped to the entrance door and rang a bell, then was escorted by a teenage boy to a small but modern reading room. Approaching the reference desk, she filled out two document request cards and handed them to a girl with short red hair.

“The papers of Archbishop Randall Davidson, for the period of January through July 1916,” the girl read with interest, “and any files regarding First Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener.”

“I realize the latter request may be a bit unlikely, but I wish to at least attempt an inquiry,” Julie said.

“We can perform a computerized search of our archives database,” the girl replied without enthusiasm. “And what is the nature of your request?”

“Research for a biography of Lord Kitchener,” Julie replied.

“May I please see your reader ticket?”

Julie fished through her purse and handed over a library card, having utilized the Lambeth archives on several occasions. The girl copied her name and contact information, then peered at a clock on the wall.

“I’m afraid we’ll be unable to retrieve these documents before closing time. The data should be available for your review when the library reopens on Monday.”

Julie looked at the girl with disappointment, knowing that the library would still be open for another hour.

“Very well. I will return on Monday. Thank you.”

The red-haired girl clutched the document request cards tightly in her hand until Julie left the building. Then she waved the teenage boy to the counter.

“Douglas, can you please watch the desk for a minute?” she asked in an urgent tone. “I need to place a rather important phone call.”

Читать дальше