“Morning, Juan,” Mike Trono greeted. Trono was in his mid-thirties, with a slender build and thin straight brown hair. “I haven’t had a chance to ask, how’d you like Vermont?”

Trono was a native of the Green Mountain State.

“Beautiful, but the roads are atrocious.”

“Ah, potholes and frost heaves — oh, how I don’t miss thee.”

“You up for this?”

“Are you kidding me? I live for wreck diving. I spent my last vacation exploring the Andrea Doria .”

“That’s right. Didn’t Kurt Austin lead that trip?”

“Yeah. It was his second time down to her.”

A new voice, one with a refined English accent, intruded. “There are simply too many type A personalities aboard this ship.”

“Hello, Maurice,” Juan greeted the Oregon ’s chief steward.

It didn’t matter that it was barely past five in the morning or that news of the discovery was less than fifteen minutes old, the retired Royal Navy man was dressed as elegantly as ever in razor-creased black slacks, a snowy white button-down shirt, and shoes so polished, they’d shame a Marine honor guard.

He had a white towel draped over one arm and carried a domed silver serving tray. He set down a carafe of black coffee and removed the dome. The tempting odor of scrambled eggs and country sausage beat back the briny scent of the sea that permeated the sub bay.

After they ate, both men stripped down and donned thermal diving underwear and socks. Then came the Ursuit Cordura FZ dry suits. These suits were of one-piece construction that left only the face exposed. That would be covered with dive helmets outfitted with integrated communications gear. A computerized voice modulator would null some of the effects of breathing helium, but both men would still be left sounding like an alto-voiced Mickey Mouse.

While they were suiting up, Eddie had performed his pre-dive checks, and the Nomad submersible was lowered into the water. Additional trimix tanks were attached to hard points on the hull so the two divers wouldn’t need to use their own supply until they were on the bottom.

“How you coming?” Cabrillo asked his dive partner.

“Good to go.”

Juan flashed Mike the universal OK sign for divers, pressing index finger to thumb, and pulled his helmet over his head. Mike did the same. The two took a couple of tentative breaths and made adjustments as needed.

“And a very good morning to the Lollipop Guild,” Max Hanley called from his station in the op center.

“Very funny,” Juan retorted, but his irritation went unheard because of his comical voice.

“Just so you know, the forecast is for light wind, and a sea running barely two feet. But be advised, you’ve got a five-knot current out of the south on the bottom. Get careless and you’ll be gone.”

“Roger that,” the two men acknowledged at the same time.

“Bus driver, you ready?” Cabrillo asked Eddie Seng.

“Say the word.”

“We’re going in.”

Juan and Mike threw each other another OK sign and unceremoniously rolled into the Atlantic’s cool embrace. Both were quick with inflating their suits and adjusting their buoyancy so they hovered like dark jellyfish just below the surface. They found handholds along the side of the Nomad and switched their air feeds to the spare tanks attached to her.

“Let’s go.”

“Hold on tight. Nomad, release.” A pause. “We are clear.”

Bubbles erupted around the submersible as Eddie purged her tanks and the thirty-foot mini-sub began its descent to the seafloor and whatever lay hidden on the derelict mine tender.

Cabrillo could feel pressure building on his suit and knew it would approach two hundred pounds per square inch when they reached the wreck. He continuously added argon gas to keep the material from crushing in on him. The cold temperature wasn’t a problem now, but it would eventually start seeping through the protective layers and leach heat first from his skin and then his very core.

Down they dropped, the blue-gray water of a dawn dive giving way to midnight blue and finally true black as they settled deeper and deeper. There was no sense of movement to their descent except for the steadily building current that swept tropical waters out of the Caribbean along the East Coast and eventually to Northern Europe.

Juan kept a constant vigil over his equipment, checking valves and his dive computer for time and depth and other details. He also checked in with Max and Eddie at regular intervals and maintained visual confirmation that his dive partner was okay. Laxity anywhere is dangerous. On a dive, it is deadly.

“Bottom coming up in fifty feet,” Eddie announced. “I’m going to switch on the lights.”

As powerful as they were, the xenon lamps mounted on the forward part of the submarine could throw a corona of light only twenty feet. It showed the ocean was full of snow — tiny particles of organic matter that continuously rained down from the surface, only this was much worse because of the current. Cabrillo had experienced this phenomena many times, but this trip was like trying to peer through a blizzard.

“Visibility sucks,” Mike complained.

“Say again,” Max radioed.

“No visibility,” Juan enunciated slowly.

“Copy that. Poor vis.”

“We’re coming down about fifty feet off the ship,” Eddie said. “I’ve got it on lidar. The vessel itself is eighty feet long, but she’s trailing a good two hundred feet of old fishing nets that’re snagged around her hull.”

A burst of silt erupted around the hull when Eddie gunned the sub’s motors a bit too hard. “Oops. Sorry about that.”

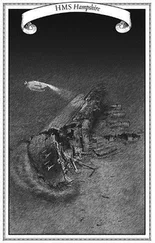

The submersible crawled out of a billowing cloud of sand that seemed to be flushed away by the Gulf Stream. Cabrillo got his first look at the wreck with his own eyes. The old Navy ship appeared as haunted and forlorn as any wreck he’d seen, and with the rotting nets waving in the current, she looked like an old castle draped in cobwebs. He felt a shiver run up his spine that had nothing to do with the temperature.

The ship itself was a slender, arrow-bowed craft, with good proportions to her superstructure and a single up-and-down funnel placed just aft of amidships. She had no name, but under the accumulated rime of sea growth the number 821 could be seen painted next to her main anchor hawsehole. It appeared that she’d settled evenly. There were no crushed hull plates, but the superstructure was showing signs of decay as portions of some decks had collapsed after nearly seventy-five years of the ocean’s corrosive assault.

“Would you guys turn on your helmet cams so we can get a visual up here?” Max prompted.

Juan turned on both his camera and his own lights while Mike Trono did the same.

As they edged closer, more details emerged, and Juan saw the odd frame built around the ship that Eric Stone had mentioned. The metal trusswork looked like it extended to just below the waterline and covered the entire ship in what was essentially a cage with openings of about two feet square. It was going to be a tight fit to get through the frame and actually explore the ship.

There was something really strange about the structure, whose purpose he couldn’t begin to guess. And then it occurred to him. While the rest of the ship was rust-streaked and matted with marine growth, the frame was shiny, and not a single organism had tried to make it their home. No clams grew there, like the colonies infesting the ship’s deck, no starfish clung to it, not even a stray coral polyp. It was as if the sea creatures shied away from the metal scaffold.

“Mike,” Juan called, “take a sample of that frame. Priority one.”

“Copy. You want a sample of the frame,” Trono repeated back so there was no confusion.

Читать дальше