Patrick O'Brian - Post captain

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Patrick O'Brian - Post captain» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Книги. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Post captain

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Post captain: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Post captain»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Post captain — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Post captain», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mr Simmons advanced to the break of the quarterdeck, glancing quickly up and down, said, ‘Thick and dry for weighing,’ and then, before the rush of feet had died away,

‘Make sail.’ No more. Instantly the shrouds were dark with men racing aloft. Her topsails, her deep, very well cut topsails were let fall in silence, sheeted home, the yards hoisted up, and the Lively, surging forward, weighed her anchor without a word. But this was not all: even before the small bower was fished, the jib, forestaysail and foretopgallant had appeared and the frigate was moving faster and faster through the water, heading almost straight for the Nore light. All this without a word, without a cry except for an unearthly hooting of Woe, woe, woe high in the upper rigging. Jack had never seen anything like it. In his astonishment he looked up at the main topgallant yard, and there he saw a small form hanging by one arm;

it swung itself forward on the roll of the ship and fell in a sickening curve towards the maintopmaststay. Almost unbelievably it caught this rope, and then, altogether unbelievably, shot up from one piece of rigging to another to the fore-royal and sat there.

‘That is Cassandra, sir,’ said Mr Simmons, seeing Jack’s face of horror. ‘A sort of Java ape.’

‘God help us,’ said Jack, recovering himself. ‘I thought it was a ship’s boy gone mad. I have never seen anything like it - this manoeuvre, I mean. Do your people usually make sail according to their own notions?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said the first lieutenant, in civil triumph.

‘Well. Very well. The Lively has her own way of doing things, I see. I have never seen . ..’ The frigate was heeling to the breeze, marvellously alive, and he stepped to the taffrail, where Stephen, dressed in a sad-coloured coat and drab small-clothes, stood conversing with Mr Randall, bending to hear his tiny pipe. Jack looked at the dark water slipping fast by her side, curving deep under the chains; she was making seven knots already, seven and a half. He looked at her wake, fixing an anchored seventy-four and a church tower - hardly a trace of leeway. He leant over the larboard quarter, and there, one point on the larboard bow, was the Nore light. The wind was two points free on the starboard tack, and any ship he had sailed in would be aground in the next five minutes.

‘You are happy about your course, Mr Simmons?’ he said.

‘Quite happy, sir,’ said the first lieutenant.

Simmons knew his ship, that was obvious: he most certainly knew her capabilities. Jack repeated this - he was convinced of it; it must be so. But the next five minutes were as unhappy as any he had ever spent -this beautiful, beautiful ship a mere hulk, dismasted, bilged . . . During the moments when the Lively was racing through the turbid shoaling water at the edge of the bank and where a trifle of leeway would wreck her hopelessly, he did not breathe at all. Then the bank was astern.

With as much impassivity as he could summon he drew in the good sparkling air and desired Mr Simmons to set course for the Downs, where he was to pick up some supernumeraries and, if Bonden had not vanished, his own coxswain, seeing that Captain Hamond had taken his with him to London. He set to pacing the windward side of the quarterdeck, keenly watching the behaviour of the Lively and her crew.

No wonder they called her a crack frigate: her sailing qualities were quite out of the ordinary, and the smooth quiet discipline of her people was beyond anything he had seen: her speed in getting under way and making sail had something unnatural about it, as eerie as the cry of the gibbon in the rigging.

The familiar low, grey, muddy shores glided by; the sea was a hard metallic grey, the horizon in the offing ruled sharply from the mottled sky, and the frigate ran on, the wind now one point free, as though a precise, undeviating rail were guiding her. Merchantmen were coming in for the London river, four sail of Guineamen, and a brig of war for Chatham, apart from the usual hovellers and peterboats: how flabby and loose they looked, by comparison.

The fact of the matter was that Captain Hamond, a gentleman of a scientific turn of mind, had chosen his officers with great care and he had spent years training his crew; even the waisters could hand, reef and steer; and for the first years he had raced them mast against mast in furling and loosing sail, putting them through every manoeuvre and combination of manoeuvres until they reached equality at a speed that could not be improved upon. And today, jealous for the honour of their ship, they had excelled themselves; they knew it very well, and as they passed near their acting-captain they glanced at him with discreet complacency, as who should say, ‘We showed you a thing or two, cock; we made you stretch your eyes.’

What a ship to fight, he reflected: if he met one of the big French frigates, he could make rings round her, beautifully built though they were. Yes. But what of the Livelies themselves? They were seamen, to be sure, quite remarkable seamen; but were they not a little elderly, on the whole, oddly quiet? Even the ship’s boys were stout hairy fellows, rather heavy for lying out on the royal yards; and most of them talked gruff. Then there were a good many brown and yellow men aboard. Low Bum, who was now at the wheel, steering wonderfully small, had had no need to grow a pigtail when he entered at Macao; nor had John Satisfaction, Horatio Jelly-Belly or half a dozen of his shipmates. Were they fighting men? The Livelies had had none of the incessant cutting-out expeditions that made danger an everyday affair and so disarmed it: circumstances had been entirely different - he should have read her log to see exactly what she had done. His eye fell on one of the quarterdeck carronades. It was painted brown, and some of the dull, scrubbed paint overlapped the touch-hole. It had not been fired for a long while. Certainly he should look at the log to see how the Livelies spent their day.

On the leeward side Mr Randall told Stephen that his mother was dead, and that they had a tortoise at home; he hoped the tortoise did not miss him. Was it really true that the Chinese never ate bread and butter? Never, at any time whatsoever? He and old Smith messed with the gunner, and Mrs Armstrong was very kind to them. Plucking at Stephen’s hand to draw his attention, he said in his clear pipe, ‘Do you think the new captain will flog George Rogers, sir?’

‘I cannot tell, my dear. I hope not, I am sure.’

‘Oh, I hope he does,’ cried the child, with a skip. ‘I have never seen a man flogged. Have you ever seen a man flogged, sir?’

‘Yes,’ said Stephen.

‘Was there a great deal of blood, sir?’

‘Indeed there was,’ said Stephen. ‘Several buckets full.’ Mr Randall skipped again, and asked whether it would be long to six bells. ‘George Rogers was in a horrid passion, sir,’ he added. ‘He called Joe Brown a Dutch galliot-built bugger, and damned his eyes twice: I heard him. Should you like to hear me recite the points of the compass without a pause, sir? There is my Papa beckoning. Goodbye, sir.’

‘Sir,’ said the first lieutenant, stepping across to Jack, ‘I must beg your pardon, but there are two things I forgot to mention. Captain Hamond indulged the young gentlemen with the use of his fore-cabin in the mornings, for their lessons with the schoolmaster. Should you wish to continue the custom?’

‘Certainly, Mr Simmons. A capital notion.’

‘Thank you, sir. And the other thing was that we usually punish on Mondays in the Lively.’

‘On Mondays? How curious.’

‘Yes, sir. Captain Hamond thought it was well to let defaulters have Sunday for quiet reflection.’

‘Well, well. Let it be so, then. I had meant to ask you what the ship’s general policy is, with regard to punishment. I do not like to make any sudden changes, but I must warn you, I am no great friend to the cat.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

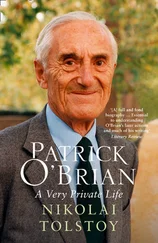

Похожие книги на «Post captain»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Post captain» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Post captain» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.