The “Falstaff” is a prominent feature of the entrance to Canterbury, and forms, with the stern drum towers of Westgate, built about 1380, as fine an entrance to a city as anything to be found in England. The present sign of the house derives from the instant and extraordinary popularity that Shakespeare’s Fat Knight obtained, from his first appearance upon the Elizabethan stage. The present “Falstaff” is a very spirited rendering, showing the Fat Knight with sword and buckler and an air of determination, apparently “just about to begin” on those numerous “men in buckram” conjured up by his ready imagination on Gad’s Hill. There is an air about this representation of him irresistibly reminiscent of that song which gave British patriots in 1878 the name of “Jingoes.” There are no patriots now: only partisans and placemen—but that is another tale. This Falstaff evidently “don’t want to fight; but by Jingo”—well, you know the rest of it.

SIGN OF THE “FALSTAFF,” CANTERBURY.

Not only pilgrims and travellers from London to Canterbury were thus looked after, but those also coming the other way, and thus we find a Maison Dieu established at Dover in the reign of King John by that great man, Hubert de Burgh, Chief Justiciary of England. A master and a staff of brethren and sisters were placed there to attend upon the poor priests and the pilgrims and strangers of both sexes, who applied for food and lodging. Kings cannot be classed in any of these categories; but they also are found not infrequently making use of the institution, on their way to or from France—and departing without a “thank ye.” The only one who seems to have benefited the Maison Dieu very much was Henry the Third, who endowed it with the tithe of the passage fare and £10 a year from the port dues.

It is scarce necessary to say who it was that disestablished the Maison Dieu. The heavy hand of Henry the Eighth squelched it, in common with hundreds of other religious and semi-religious institutions. At the time of its suppression the annual income was £231 16 s. 7 d. , representing some £2,500 in our day. The master, John Thompson, who had only been appointed the year before, was an exceptionally fortunate man, being granted a pension of £53 6 s. 8 d. a year. The buildings were then converted into a victualling office for the Navy.

At last, in 1831, the Corporation of Dover purchased them, and the ancient refectory then became the Town Hall and the sacristy the Sessions House, and so remained until 1883, when a new Town Hall was built.

Similar institutions existed at others of the chief ports. At Portsmouth was the Hospital of St. Nicholas, or “God’s House,” founded in the reign of Henry the Third by Peter de Rupibus, Bishop of Winchester. It is now the Garrison Church. At Southampton the “Domus Dei” was dedicated to St. Julian, patron of travellers, and now, as St. Julian’s Hospital and Church, is in part an almshouse, sheltering eight poor persons, and partly a French Huguenot place of worship.

The Pilgrims’ Way to Canterbury from Southampton and Winchester was never a road for wheeled traffic, and remained in all those centuries when pilgrimage was popular, as a track for pedestrians, along the hillsides. It avoided all towns, and thus precisely what those pilgrims who wearifully hoofed it all the way did for shelter remains a little obscure: although it seems probable that wayside shelters, with or without oratories attached to them, were established at intervals. Such, traditionally, was the origin of the picturesque timbered house at Compton, now locally known as “Noah’s Ark.”

Colchester was a place of import to pilgrims in old wayfaring times, for it lay along the line of the pilgrims’ trail to Walsingham. Among the inns of this town, and older than any of its fellows, but coyly hiding its antiquarian virtues of chamfered oaken beams and quaint galleries from sight, behind modern alterations, is the “Angel” in West Stockwell Street, whose origin as a pilgrims’ inn is vouched for. Weary suppliants, on the way to, or returning from, the road of Our Lady of Walsingham, far away on the road through and past Norwich, housed here, and misbehaved themselves in their mediæval way. It would, as already hinted, be the gravest mistake to assume pilgrims to have been, quâ pilgrims, necessarily decorous; and, indeed, modern Bank Holiday folks, compared with them, would shine as true examples of monkish austerity.

HOUSE FORMERLY A PILGRIMS’ HOSTEL, COMPTON.

The shrine at Walsingham, very highly esteemed in East Anglia, drew crowds from every class, from king to beggar. The great Benedictine Abbey of St. John of Colchester sheltered some of the greatest of them, while others inned at such hostelries as the “Angel,” and the vulgar, or the merely impecunious, if the weather were propitious, lay in the woods.

Pilgrims would boggle at nothing, as was well known at the time. That they could not be trusted is evident enough in the custom of horse-masters, who let out horses on hire to such travellers, at the rate of twelvepence from Southwark to Rochester, and a further twelvepence from Rochester to Canterbury. They knew, those early keepers of livery-stables, that little chance existed of ever seeing their horses again unless they took sufficient precautions. They therefore branded their animals in a prominent and unmistakeable way, so that all should know such, found in strange parts of the country, to be stolen.

Ill fared the unsuspecting burgess who met any of these sinners on the way to plenary indulgence, for they would, not unlikely, murder him for the sake of anything valuable he carried; or, out of high spirits and the sheer fun of the thing, cudgel him into a jelly; arguing, doubtless, that as they were presently to turn over a new leaf, it mattered little how soiled was the old one. Drunkenness and crime, immorality, obscenity, and licence of the grossest kind were, in fact, the inevitable accompaniments of pilgrimage.

THE “STAR,” ALFRISTON.

Although East Anglia was in the old days more plentifully supplied with great monastic houses than any other district in England, the destruction wrought in later centuries has left all that part singularly poor in the architectural remains of them: and even the once-necessary guest-houses and hostels have shared the common fate. That charming miniature little house, the “Green Dragon” at Wymondham, in Norfolk, may, however, as tradition asserts, have once been a pilgrims’ inn dependent upon the great Benedictine Abbey, whose gaunt towers, now a portion of the parish church, rise behind its peaked roofs.

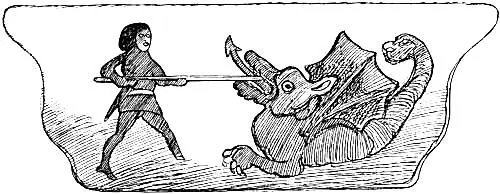

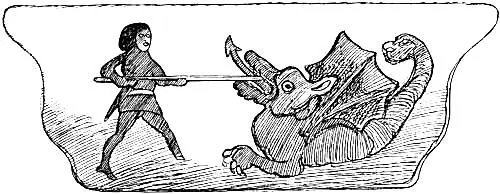

CARVING AT THE “STAR,” ALFRISTON.

The beautiful little Sussex village of Alfriston—whose name, by the way, in the local shibboleth, is “Arlston”—a rustic gem not so well known as it deserves, possesses a very fine pilgrims’ inn, the “Star,” a relic of old days when the bones of St. Richard of Chichester led many a foot-sore penitent across the downs to Chichester, in quest of a clean spiritual bill of health. Finely carved woodwork is a distinguishing feature of this inn, whose roof, too, has character of its own, in the heavy slabs of stone that do duty for slates, and bear witness to the exceptional strength of the roof-tree that has sustained them all these centuries. The demoniac-looking figure seen on the left-hand of the illustration is not, as might perhaps at first sight be supposed, a mediæval effigy of Old Nick, or an imported South Sea Islander’s god, but the figure-head of some forgotten ship of the seventeenth century, wrecked on the neighbouring coast, off Cuckmere Haven. Ancient carvings still ornament the wood-work of the three upper projecting windows, the one particularly noticeable specimen being a variant of the George and Dragon legend, where the saint, with a mouth like a potato, no nose to speak of, and a chignon, is seen unexpectedly on foot, thrusting his lance into the mouth of the dragon, who appears to be receiving it with every mark of enjoyment, which the additional face he is furnished with, in his tail, does not seem to share. The left foot of the saint has been chipped off. All the exterior woodwork has been very highly varnished and painted in glaring colours, from the groups under the windows to the green monkey and green bear contending on the angle-post for the possession of a green trident.

Читать дальше