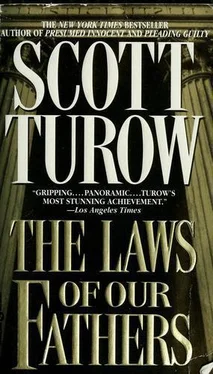

Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Laws of our Fathers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Laws of our Fathers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Laws of our Fathers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Laws of our Fathers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Laws of our Fathers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We were in the bedroom by now, with its porthole window and glossy yellow enamel on the fleur-de-lis patterns in the walls. The heater spurted up out in the hall. I crumbled sadly on the bed.

‘I mean, really,' I said after another silence in which neither of us had the bravery to look at the other. 'What about us? Don't you think about it?'

'God, baby, I have. I have. Of course, I have. But it's not a thinking thing. I have to feel that it's right. To go up there – I might, but it's such an enormous step. For me. It means I'm following you. It means it's your stuff, not my stuff. It means I'm in purgatory, because you are. There are so many problems. I just have to work it through. You understand. I know you do.'

I couldn't believe it. The Future. The dread spot where my life fell apart. I was finally there.

A couple of weeks after New Year's, the phone rang in the middle of the night. Waking, I first thought something must have happened to one of my parents. But it was the line they didn't use that was ringing. Lucy was on the other end, asking me to come over, her voice shrill with distress.

'Bad trip,' she explained. 'Really bad.'

I'd never known Hobie to bum out. Senior year, he was heavy into hallucinogens – LSD, psilocybin, magic mushrooms. He loved to borrow a motorcycle and cruise the wooded hills of Greenwood County. I went along once and had a peak experience, my spirit seeming to flood out of me, crystallizing in the treetops of the oaks, where it shimmered magically as the undersides of the leaves spun in the wind. But for the most part I stayed away from acid, wary of confronting my own spooks.

When I reached their apartment on Grand Street in Damon, I found Lucy cowering behind the door, shooing away their dog, a large cream-colored husky named Mighty White. Hobie's late-term cramming had left the apartment looking as if a twister had hit. Throughout college, Hobie had indulged Gurney, his father, in a pharmacist's predictable dream that his son would go to medical school. Those of us who knew Hobie well realized his only interest was in getting his hands on his own prescription pad. In the end, he chose law school both to pacify his parents and because he'd heard the only required work was a single exam in each course. He didn't want to waste his time on papers and midterms just to get drafted. But now that the lottery had freed him, he had to learn something about law fast. The first exams were a few days away. His casebooks and notes were thrown all over the living room, and the place reeked of cigarettes, a habit he took up at the end of each semester, asking all his friends to save, from their flights home over the holidays, the little four-packs that the airlines handed out with meals. I'd seen this routine many times at Easton: Hobie begging every guy in the dorm for notes on the classes he'd cut, the texts he'd never bought. Ultimately, he always made the Dean's List, with grades higher than mine. At the moment, Hobie sat across the room on the sofa, a secondhand piece with rolled arms and a campy countrified floral pattern. He was sobbing. His cheeks shone and his arms hung loose between his knees. At the same time, he remained fixed on the TV, which, pursuant to the needs of his lifestyle, was positioned only a few steps from him. An old movie was running. Hepburn and Tracy.

Lucy explained that Hobie was enduring the results of playing chemistry lab with his own head: he had dropped some acid and taken a noseful of Cleveland's snow as a garnish.

'He's been crazy,' she said. 'Throwing stuff? Screaming?'

'Have we got like a theme?'

'You'll hear.' She rolled her eyes in a rare show of exasperation.

Near the sofa, a picture of Hobie's family was smashed in its frame. An ashtray had been emptied. I sat down next to him carefully. He was wearing a T-shirt of his own design, which he had produced and marketed at Easton – an anatomically perfect heart and lungs brightly serigraphed above a black legend which read 'Be My Transplant.'

'So, Mr Gordon, any sign of the evil emperor Ming?' In his eyes, you could see my question lost like quicksilver in some crack in his brain. Somehow it was always a gas for me when Hobie was fucked up and I was straight, making me, for a brief interval, the master in our tangled relationship. 'So like what's flipping across the screen, dude, got you so unhappy?'

'Hey, man, you know.' Blasted by the drugs, he was softer, deprived of his usual hard-shell hipness. His round face was puffed up by tears.

'Are you in-body?' I asked. Hobie had experienced reliable sensations two or three times during acid trips of being someone else: a fourteenth-century woman in Avignon who worked on the weaving of one of the Papal tapestries, and a Nepalese peasant named Prithvi Pradyumna, whose life each day, treading behind his oxen, was consumed with unrelenting bitter anguish that his brother, rather than he, had been permitted to become a monk. His eyes flickered up now.

'It's all bad,' he told me.

'You mean the dope. What are we saying?'

'Dope? Huh? It's dope. It's everything. It's being skulled and crazy. It's all the dope.'

I agreed: he did too much. I told him that. Immediately, he began to rage at me.

'No! You know why I been stoned for five years, man? You know?' He thundered to his feet abruptly and loomed over me. 'I've been killing the pain, boy! I've been ignoring the facts! Did you know that?' 'No.'

'Did you know that?' he screamed with his substantial arms outstretched. Lucy peeked in from the kitchen. Now that I had arrived, she had given way. She was crying, her face a mess of melted liner. 'Man, there is something I ain't never wanted to tell myself. And you know what it is? Do you know what it is?'

'No.'

'He doesn't know what it is,' Hobie bellowed to the ceiling. Up there, he had glued one of his casebooks with a note reading 'Law is a natural high' dangling from a corner. He faced me so suddenly that I flinched. 'I'm a black man,' he declared and briefly descended into a terrible grief-strained spasm of tears. 'Do you know what it means to be a black man? Do you know?'

Growing up in my father's home, I'd felt a special sense for the brute pain of oppression. I began to remind Hobie of my efforts, the meetings, the marches I'd made with his parents. It only infuriated him. 'Don't tell me about that! You think cause you went marching up and down the street askin people not to be so mean, I have to send you a fucking thank-you note? What'd that ever do, man? That was nothing more than a walk in the fresh air.' Hobie kicked the coffee table, a miserable piece of cheap wood with a scarred veneer, so that it jumped against my knees.

'I know the world's fucked up, man. But it's changing. It's changed, for Chrissake. Twenty years from now, man, there isn't going to be a slum left in this country. Poor Negroes -'

'Blacks! Blacks, man.'

It was Hobie's dad, Gurney, in his avuncular way, who'd taught me one day in his drugstore when I was seven to say 'Negro' rather than 'colored.'

'Right, blacks. Blacks, poor blacks are like immigrants who got off the boat in 1964. They're newly arrived. You think they won't jump into the melting pot, too? They'll stop speaking dialect, they'll-'

' "Di'-alect"? Man, that's our language. That's our culture. Shit! You know, I just can't talk to you about this.' Both Lucy and the dog cringed by the wall as Hobie strode from the room. In time, I found him on the back porch, a rickety wooden construction off the kitchen, where the floor was reinforced to hold a washer. He was ripping wet laundry out of the machine. He picked up three or four items, slinging them without aiming across the bright kitchen. A shirt stuck to the refrigerator. A sock hung on the clock. A pair of jeans hit the yellow wall with a moist thwack and after a time crawled down to the floor, leaving a glistening trail. He reared up in fury when he saw me again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Laws of our Fathers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.